Trinidad and Tobago's close proximity to the equator enables the country to have two climate types producing two opposing seasons. These seasons are differentiated by distinct dry and wet season regimes. The dry season which occurs during January to May is symbolized by a tropical maritime climate that is characterized by moderate to strong low level winds, warm days and cool nights, with rainfall mostly in the form of showers due to daytime convection. A modified moist equatorial climate characterized by low wind speeds, hot humid days and nights, a marked increase in rainfall which results mostly from migrating and latitudinal shifting equatorial weather systems, symbolizes the wet season during June to December. The periods late May and December are considered as transitional periods to the wet and dry seasons respectively. Variations in these two climatic seasons between the islands of Trinidad and Tobago are primarily as a result of difference in land size, orography, elevation, orientation in terms of the trade winds and geographical location. Within the wet season is the hurricane season which runs from June to November, peaking between August and October. Trinidad’s geographical location puts it on the southern periphery of the North Atlantic hurricane basin. As such, Trinidad is not affected directly by storms as frequent as Tobago; however, peripheral weather associated with the passage of tropical storm systems impacts Trinidad and Tobago similarly.

Trinidad and Tobago's daily temperature cycle is more pronounced than its seasonal cycle. The long term mean (1971 - 2000) annual maximum and minimum temperatures are 31.3 Celsius and 22.7 Celsius respectively with a mean daily temperature of 26.5 Celsius. Generally, the wet season temperatures are warmer than the dry season temperatures with September being the warmest wet season month and March the warmest in the dry season. Annually and seasonally Trinidad is wetter than Tobago; however, the rainfall pattern in both islands display a distinct bi-modal behaviour with early (June) and late(November) rainfall season maxima occurring. Trinidad's primary rainfall mode occurs in June while Tobago's primary mode occurs in November. The annual rainfall totals are largely driven by multiple competing weather features, chief of which are the latitudinal position and strength of the North Atlantic Sub-Tropical High (NASH) pressure cell, meridional shift of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), westward propagating Tropical Waves and cyclones (depression, storms, hurricanes), Mid-Atlantic upper level trough system, localized sea-breeze effects, cloud clusters driven by large scale low level convergence and orography. Generally, during the dry season the NASH pressure cell center migrates more southerly than during the wet season and expands equator-ward resulting in generally subsiding air, low level moisture evacuation and strong trade winds over Trinidad and Tobago, which result in a drier state of the atmosphere. Usually during May, the slow but sure shifting of the NASH pole-ward with winds on its southern flank converging more, allows rain bearing systems such as the ITCZ and Tropical waves to penetrate northward and eastward; resulting in the transition to and eventual onset of the wet season regime.

Climate Variability refers to departures from the mean position and higher order statistics such as standard deviations, as well as changes in the occurrences of extremes. Moreover, it is used to indicate departures of the mean etc over a given time period (for instance a month, a season, a year) from the long term statistic for a matching time period. Climate variability is thus a measure of the departures which are usually called anomalies. Climate variability is caused by natural occurring internal processes which occur on all time and spatial scales outside of that of individual weather events, and involves many modes of variability involving components of the climate systems such as the atmosphere and the ocean. An example of a naturally occurring internal process which drives climate variability in Trinidad and Tobago is the coupled ocean/atmosphere El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO- El Nino or La Nina) phenomenon.

Climate change refers to a change in the mean condition of the climate that can be identified by a change in the mean and or variability of its properties that is statistically significant and this change must continue for an extended period, typically decades or longer. It may be due to naturally occurring internal processes such as volcanic eruptions which can act to cool the atmosphere; or external forcing such as changes in solar radiation received at the earth surface which can be influenced for instance by change in the tilt of the earth axis away from its orbital plane which occurs naturally. Naturally occurring climate variability can also induce climate change. Climate change may also be due to persistent external influences which do not occur naturally such as the change in the composition of the atmosphere or change in land use generated by human activity such as the burning of fossil fuel and deforestation.

The major difference between climate variability and climate change is the persistent nature of the anomaly and the fact that the change cannot be explained by naturally occurring internal variability processes alone. For instance, rare events occur more often or less often e.g. the maximum temperatures increasingly breaking records each year or nights are consistently becoming warmer each year. Climate change detection is the process of demonstrating that the climate has changed in some defined statistical sense without providing a reason for the change. Climate change attribution is the process of establishing the most likely cause for the detected change with some defined level of confidence.

1. Statement of the problem

The intent of this document is to facilitate monitoring and assessment of mild to extreme dry spells in Trinidad and Tobago; and in the process assist in reducing crisis responses to such events. Motivation for this policy document resulted from the reality that varying degrees of dry spells in Trinidad and Tobago impact water resources management, agricultural production, health and well-being as well as other areas. More importantly, extreme dry spells such as drought conditions can have related ripple effect on the economy, in areas such as agriculture and related sectors, including forestry, especially in the circumstances of projected climate change. In the context of an increasing local population, a renewed push towards agriculture productivity, the associated increase in demand for potable water, and the underlying vulnerability from extreme dry spell impacts, it is imperative that as a national meteorological service, proper monitoring of dry spells with regular updates be established. This would require a dry spell or drought early warning system that incorporates monitoring, assessment and a well developed information delivery system.

Current operative procedures for determining different levels of dry spells are not adequately defined. Consequently, the meteorological service intention of moving towards science based dry spell and drought monitoring is somewhat stymied. This policy document seeks to remove the gap and is expected to serve as a basic policy guidance document on essential rainfall deficit or surplus monitoring aimed at ensuring that the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service (TTMS) offers quality advice to key stakeholders and decision makers. Basic international and regional standards and guidelines for monitoring and assessing rainfall deficits and surpluses have long been in place under the auspices of the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) and have undergone upgrade and repositioning from time to time. This document seeks to similarly follow this practice at the local level.

2. Introduction

Before implementing any dry spell and drought policy it is important to understand the difference between the two features, the complexity of the latter and distinguish between the various types of drought. According to WMO a dry spell is a period of at least 15 consecutive days none of which received 1 mm or more (UK) or a period lasting not less than two weeks during which no measurable rainfall is recorded (US). Generally the term is applied to less extensive and less severe conditions than drought. Drought on the other hand is broadly defined by the WMO as an extreme climatic condition that results from an extended period of decrease rainfall that is significantly less than the expected amount for a specific period and is not enough to meet the demands of society activities as well as the environment. In essence, drought is an extended, unusually dry period when there is not enough water to meet the normal needs of users and is not just about low rainfall.

Drought is very application specific and has different meanings based on water needs of various sectors. For instance, climatologists keep a close watch on the extent and severity of drought in terms of rainfall deficit; agriculturalists consider the impact of water shortage on crop growth; hydrologists evaluate ground water levels; and sociologists classify it on social expectations and beliefs. Accordingly, various types of droughts exist such as meteorological, agricultural, hydrological and socio-economic. This policy document deals specifically with meteorological drought and associated dry spells. In guiding National Meteorological Services (NWS), WMO suggests that the Standard Precipitation Index (SPI) become the primary index to monitor dry spells and characterize meteorological drought. The TTMS adopts the SPI as its primary dry spell and drought monitoring index and will supplement its dry spell, drought monitoring and assessment process from time to time with any other indices which it may deem fitting for effective dry spell and drought assessment. To highlight what is broadly considered a meteorological drought in the context of other droughts the following definitions are offered.

3. Definitions

Meteorological drought refers to short-period droughts or dry spells and is based solely on deficiency in rainfall that is far below the expected average (usually the period long term average) over a specific extended period of time, usually a few months, a season, to a few years. It is expressed solely on the basis of the degree of dryness (often in comparison to some "normal" or average amount) and the duration of the dry period. Since atmospheric conditions which results in rainfall deficiencies vary according to regions, meteorological drought is region specific and as such its characterization must take into consideration a profound understanding of the climatology of the particular area. It may consider: the number of days with rainfall below some specified threshold or the actual rainfall departures from average totals on monthly, seasonal or yearly time scales.

AGRICULTURAL DROUGHT

Agricultural drought is defined by the measure of the availability of soil water to plants or animals and occurs when there is not enough rainfall, soil moisture and difference between actual and potential evapo-transpiration to meet the needs of a specific plant or animal at a particular time. It can take place simultaneously or a little before or after a meteorological drought.

HYDROLOGICAL DROUGHT

Hydrological drought refers to deficits in surface and sub-surface water supplies based on measurements of stream flow, lake, reservoir and groundwater levels when rainfall is deficient during an extended period of time. Hydrological droughts are usually out of phase or lag the occurrence of meteorological and agricultural droughts.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DROUGHT

Socio-economic drought definitions are associated with the effect of supply and demand of a product with elements of meteorological, agricultural and hydrological drought. Socio-economic drought occurs when demand for an economic good exceeds supply as a result of physical water shortage that is weather related and starts to affect people, both individually and collectively.

4. TTMS Meteorological Drought and Dry Spell Characterization Methodology

Defining a local meteorological drought on the basis of number of days with rainfall below some specified threshold is unrealistic for Trinidad and Tobago given that extended (14 to 20 consecutive day- a dry spell) number of days without rainfall is a common feature of the local dry season climatology. It is also not unusual to experience extended number of dry days (Petit Careme) in the wet season. A more realistic method is actual rainfall departures from average totals on monthly or seasonal time scales given that it is not normal to have a month much less a season without measurable rainfall in the local dry season, climatology.

Operationally, the TTMS meteorological drought and dry spell characterization seeks to identify the onset, duration and severity of the event through the comparison of the existing situation with the climatological average based on the 30 year climatological period or longer in accordance with the WMO recommendations.

In utilizing the SPI as the primary dry spell and drought monitoring tool, the TTMS take note of, and adhere to the following principles about the SPI from WMO (2012), McKee (1993) and Guttman (1999) : The SPI provides a comparison of the rainfall over a specific period (e.g. a specific 1-, 2-, 3-, 6-, 12-month period) with the rainfall totals for the corresponding period for all the years in the climatological record.

The SPI is a drought index based only on rainfall and represents the number of standard deviations that observed cumulative rainfall move away from the climatological or long term average for normally distributed rainfall. Since rainfall is not normally distributed, in calculating the SPI, an appropriate probability density function is estimated and a transformation is applied to the associated cumulative probability distribution so that the rainfall values follow a normal distribution.

The resulting SPI is then interpreted as a probability using the standard normal distribution (i.e., users can expect the SPI to be within one standard deviation about 68% of the time, two standard deviations about 95% of the time, etc.). Therefore, the SPI for a time scale is the probability of recording a given amount of rainfall and since the probabilities are standardized, zero SPI indicates the mean rainfall amount is expected. Negative SPI indicates expected deficit rainfall (i.e. number of standard deviations that the rainfall value would be less than the mean during the time scale considered);while positive SPI indicates surplus rainfall (i.e. number of standard deviations that the observed rainfall value would be higher than the mean during the time scale considered.

Meteorological conditions respond to rainfall anomalies on relatively short time scales. Climatologically, it has been observed locally that high temperatures, relative humidity, and wind and soil moisture, influence and is influenced by rainfall totals. This interplay is critical in assessing and monitoring the duration and severity of rainfall deficits and is given utmost consideration in characterizing what conditions need to exist locally to consider the occurrence of a Meteorological Drought in Trinidad and Tobago. The characteristics of past dry spells and the impacts caused on water catchment areas also provide a benchmark in defining the local meteorological drought and what similar conditions in the future may warrant such a declaration.

The onset, duration and severity of a local dry spell and a meteorological drought is characterized using a 2-month SPI which compares a 2-month rainfall total for a given station with rainfall total from the same 2-month for all the years on record for the same station. For instance a 2-month SPI at the end of December 2012 for the Piarco rainfall station compares the November and December rainfall totals in that year with November-December rainfall totals for all years on record for the station.

A local dry spell is considered to occur when the 2-month SPI falls between -1.0 and -1.24; a 2-month SPI between -1.25 to -1.49 is considered a moderate dry spell; a 2-month SPI between -1.50 to -1.99 over two consecutive 2-month timescale is considered a drought event; a 2-month SPI of -2.0 and less over two consecutive 2-month time scale is considered a severe drought. A 2-month SPI between -1.50 to -1.99 for one 2-month time scale is considered an incipient (budding) drought event and a drought watch or alert may be issued. Similarly, a 2-month SPI of -2.0 and less for one 2-month timescale is considered an incipient (budding) severe drought event.

5. Conclusion

Traditionally, local response to dry spells of all degrees has been through a reactionary and at times, a crisis management approach. This policy responds to the need to develop an appropriate and adequate early warning system for dry spells of all degrees. The present policy would assist in closing the gap in efficient science based monitoring of local dry spells and meteorological drought and improve assessment of these events. It would also establish a framework to advance both short and medium-term responses across all sectors to all local dry spells. A comprehensive dry spell and meteorological drought monitoring and early warning system needs a guidance policy which can deliver onset and end, determine their severity, and convey this information to key stakeholders in climate- and water-sensitive sectors in a timely manner. This policy would facilitate the delivery of such information.

6. Operational PolicyIn response to the need for a practicable dry spell and meteorological drought monitoring and forecast application, the Acting Director, Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service, recommends the following operational policy:

-

The Standard Precipitation Index (SPI) recommended by the World Meteorological Organization for monitoring dry spells and characterizing droughts by National Meteorological and Hydrological Services be adopted as the index which the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service will utilize in monitoring and attempting to predict local dry spells and meteorological droughts.

The SPI indicates how rainfall for any given duration (1-month, 2- month, 3- month, etc) at a particular observing station compares with the long-term rainfall record at the same station for the same duration. Conceptually, the SPI to be used is equivalent to the z-score used in statistics: Z-score= (X - Average) / Standard Deviation

Because rainfall is typically skewed, the rainfall data should first be transformed to fit a normal distribution by applying a gamma function. After the transformation, the SPI is to be calculated using:

SPI = (A - A) / Standard Deviation,

Where A is the total rainfall for the duration being currently considered; A is the average rainfall for the same duration over the historical records; and the SPI expresses A's distance from the average (A) in standard deviation units.

Since the SPI values are to be obtained from the standard normal distribution, the unit of the SPI should be interpreted as standard deviations.

-

The SPI should be based on rainfall only and represents the number of standard deviations that observed cumulative rainfall move away from the climatological or long term average.

-

Dry spells and meteorological droughts are to be characterized using a 2-month SPI which compares a 2-month rainfall total for a given rainfall station with rainfall total from the same 2-month for all the years on record for the same station.

-

A dry spell be characterized when the 2-month SPI falls between -1.0 and -1.24.

-

A moderate dry spell be characterized when the 2-month SPI falls between -1.25 and -1.49.

-

A drought event be characterized when the 2-month SPI falls between -1.50 and -1.99 over two consecutive 2-month SPI timescales.

-

A severe drought event be characterized when the 2-month SPI fall to -2.0 and below over two consecutive 2-month SPI timescales.

- A 2-month SPI between -1.50 to -1.99 for one 2-month time-scale be characterized an incipient (budding) drought event and a drought watch or alert be issued.

- A 2-month SPI of -2.0 and less for one 2-month time-scale be characterized an incipient (budding) severe drought event and a severe drought watch or alert be issued.

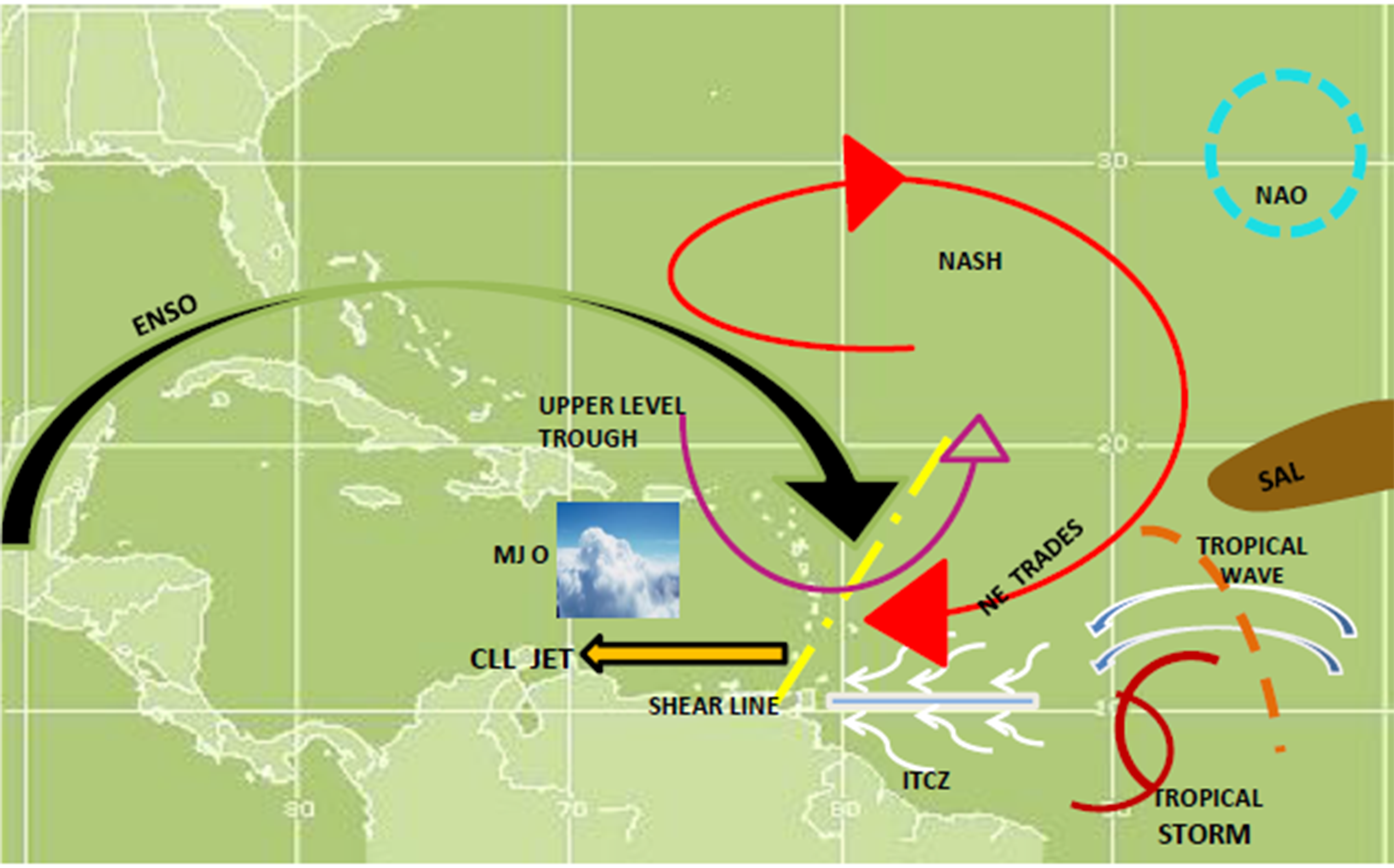

Most of the features which account for the variability of temperature and rainfall in Trinidad and Tobago originate in the tropics, but global features also impact the climatic variability. Phenomena such as El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) are two of the major drivers of climate variability in Trinidad and Tobago. It has also been shown that the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), the Saharan Air layer (SAL), tracks taken by tropical storms, migratory behaviour of the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and behaviour of the North Atlantic Sub-Tropical High (NASH) also influence the climate variability in Trinidad and Tobago.

Studies have shown that the El Nino phase of the ENSO modifies the annual cycle of rainfall over the Caribbean greatest, with varying results for different areas. The relationship between El Nino and the rainfall cycle starts with a drying trend during the latter half of the wet season which continues into the dry season and ends with a strong wet signal during the earliest period of the new wet season; this relationship was observed in Trinidad and Tobago during the 2009-2010 episode of the most recent El Nino event. With regards to La Nina, it has been found that the Southern Caribbean including Trinidad and Tobago exhibits wetter than normal late wet season and dry season; while the early wet season at the end of a La Nina event is drier than normal. The link between the NAO and Caribbean rainfall is found in the relationship between pressure systems and rainfall and temperatures in the region. A positive index is indicative of anomalously high pressures across the region resulting in a reduction in rainfall since higher pressure introduces stronger winds, more evaporation, cooler Sea Surface Temperatures (SST's), and less ascending motion. When the index is negative, rainfall in the early period of the wet season is enhanced since lower anomalous pressure introduces lighter winds, less evaporation, warmer SST's, and more ascending motion.

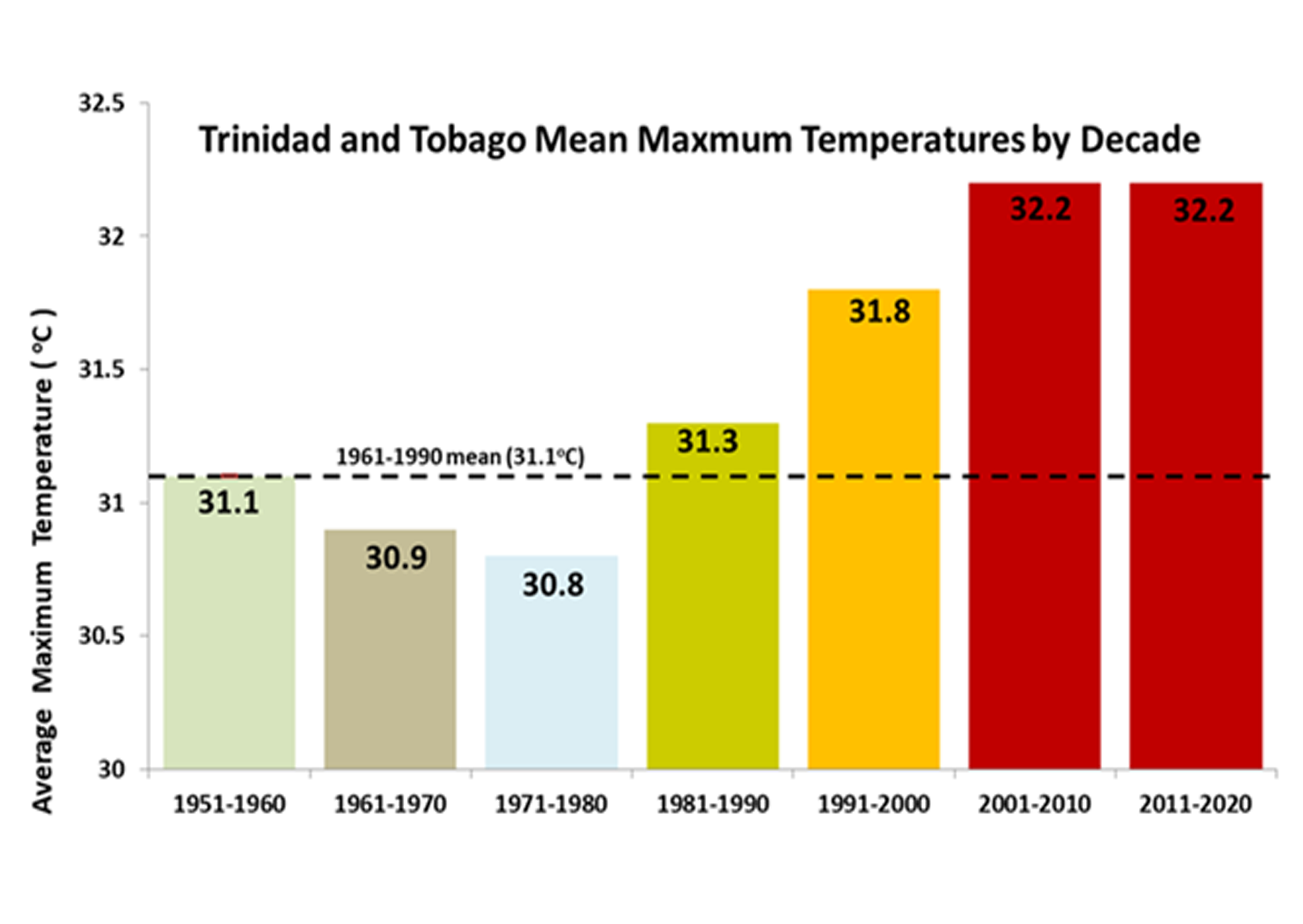

Several studies exist which have found recent changes in the climate in Trinidad and Tobago, especially with respect to temperature trends. Temperatures in Trinidad and Tobago have been found to have increased steadily from 1946 to 1995. More recently, it has been shown that over the last three decades there has been an upward trend in temperatures that is statistically significant and which has been induced by a steady increase in daily minimum temperatures ; this latter finding suggests that nights have become warmer. Other studies are also consistent with the warmer temperatures. Mc Sweeney 3using a Global Climate Model (GCM) found significant increases in the mean annual temperature in Trinidad and Tobago with an increase around 0.6 oC since 1960; an average of 0.13 oC per decade. The Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service (TTMS) also found that at Trinidad's, as well as, at Tobago's reference climatological stations, the annual mean air temperature has also warmed over the period 1981-2010 by 0.8 and 0.5 oC relative to 1961-1990 and 1971-1990, for Trinidad and Tobago respectively. The observed anomalous warming of 0.27 C per decade at the station in Trinidad and 0.17 oC per decade in Tobago are consistent with the IPCC (2007) observed 0.2 oC per decade in the Caribbean region.

Rainfall in Trinidad and Tobago has not shown as distinct a change as has been observed with temperatures. It appears that changes in rainfall differ across various parts of the country and over different time periods. During the 1960's to 80's it has been shown that Trinidad and Tobago annual rainfall totals increased, but subsequently decreased onward to the 1990's. More recently, rainfall in Penal in South Trinidad has showed a decreasing trend while at Piarco in the north, an increasing trend was observed. Another recent study conducted on behalf of the UNDP found fractional decreases in Trinidad and Tobago's rainfall over the last half century; however the trend was not statistically significant. The TTMS 8 also found that there has not been any significant change in the annual mean rainfall totals in Trinidad over the period 1981 to 2010 compared to 1961-1990; however, there were larger changes in the annual mean rainfall totals over the latter period. These changes were driven by slight increases in the frequency of extreme dry and wet years, as well as, increases and decreases in extreme wet and dry years rainfall totals respectively. In Tobago however, the rainfall pattern has shown a different behaviour;Tobago's annual mean rainfall has decline by 36.4 mm per decade during the 1981-2010 period compared to the long term average of the 1969 to 1990 period, this was driven primarily by a decrease in the number of years with near normal rainfall.

Strong El Nino events in recent years have resulted in meteorological droughts in Trinidad and Tobago. It has also been shown that the El Nino of 1997/98 and associated drought conditions in Trinidad and Tobago were responsible for the decline in sugar production during that period. The Drought event of 2010 in Trinidad and Tobago resulted in hundreds of acres of natural forest burnt. Drought conditions have also been advanced as the reason for lost of near- shore habitat due to declines in freshwater. This was aided by saline intrusion in the Southern Caribbean and Trinidad and Tobago during 2009-2010. Increased sea surface temperatures during the summer of 2005 resulted in severe coral bleaching in Tobago during the summer period. Recent increases in intense rainfall events have been associated with increased flooding in the region including Trinidad and Tobago and this has no doubt impacted fresh water impoundments and water quality. The Caribbean region experienced an average sea level rise of about 10 cm over the twentieth century due to the warming; but this rise is not uniform throughout the region.

Statistical downscaling of global climate model (GCM) HadCM3 using the A2 and B2 emission scenarios project a rise in temperature of between 1.5 - 2.0 Celsius in the Caribbean region including Trinidad and Tobago by the 2080's compared to the 1980 to 1999 period. This amounts to a projection of 0.29 Celsius per decade. If these projections are realized it is possible that an approximate 8% increase in the length of the dry season by 2050 and consequently a shorter wet season could result. Projected trends in rainfall for Trinidad and Tobago remain unclear with large uncertainties. Model consensus among 21 GCM models project annual rainfall decrease in the range of 15% for Trinidad and Tobago by the 2080's, however 3-4 of these models projected increase in annual rainfall. If the over drying trend projections are realized then it is likely that there will be intensification of dry spells and droughts in the vicinity of Trinidad and Tobago towards the 2080's.

Results from HadCM3 model downscaled for the A2 and B2 emission scenarios using the Statistical Downscale Modeling (SDSM) also project increases in the early rainy season (June – August) rainfall in Trinidad and Tobago compared to decreases in other countries in the region apart from Barbados. The drying trend projected in annual rainfall towards the 2080's is linked to a consensus in the models showing a shift to a more positive phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and El Nino like pattern in the Pacific with higher temperatures.

Based on the projections local water resources can be expected to be impacted. Increase intense rainfall events over shorter periods will result in lower surface water quality, reduction in the recharge of ground water as run off would be at a maximum; while Increase in longer dry spells and drought events coupled with warmer temperatures would increase agricultural irrigation demands,affect crop scheduling, increase heat related health impacts, coral bleaching and saline intrusion.

Recent modelling of the current and future water resource availability on several small islands in the Caribbean including Trinidad and Tobago, using a macro-scale hydrological model and the SRES scenarios (Arnell, 2004), found that many of these islands would be exposed to severe water stress under all SRES scenarios, and especially so under A2 and B25. Also, recent variations in sea level on the western Trinidad coast indicate that sea level in the north is rising at a rate of about 1 mm/yr, while in the south the rate is about 4 mm/yr; the difference being a response to tectonic movements 6. According to IPCC AR4 global Sea level is projected to rise between the present (1980-1999) and the end of this century (2090-2099) by 0.35 m(0.23 to 0.47 m) for the A1B scenario. Based on research evidence published over most recently, mean global sea level rise is projected to increase above that of IPCC AR4 projections by the end of the century7 8 9 10. Furthermore, recent studies also suggest that because of the close proximity of the Caribbean including Trinidad and Tobago to the equator, sea level rise may be more outstanding than some other regions.11 12 This suggests that, in the future, if projections materialize, coastal inundation, inland flooding, storm surge damage, and coastal erosion are likely to increase in the vicinity of Trinidad and Tobago, however uncertainty remains high.

| Introduction |

|---|

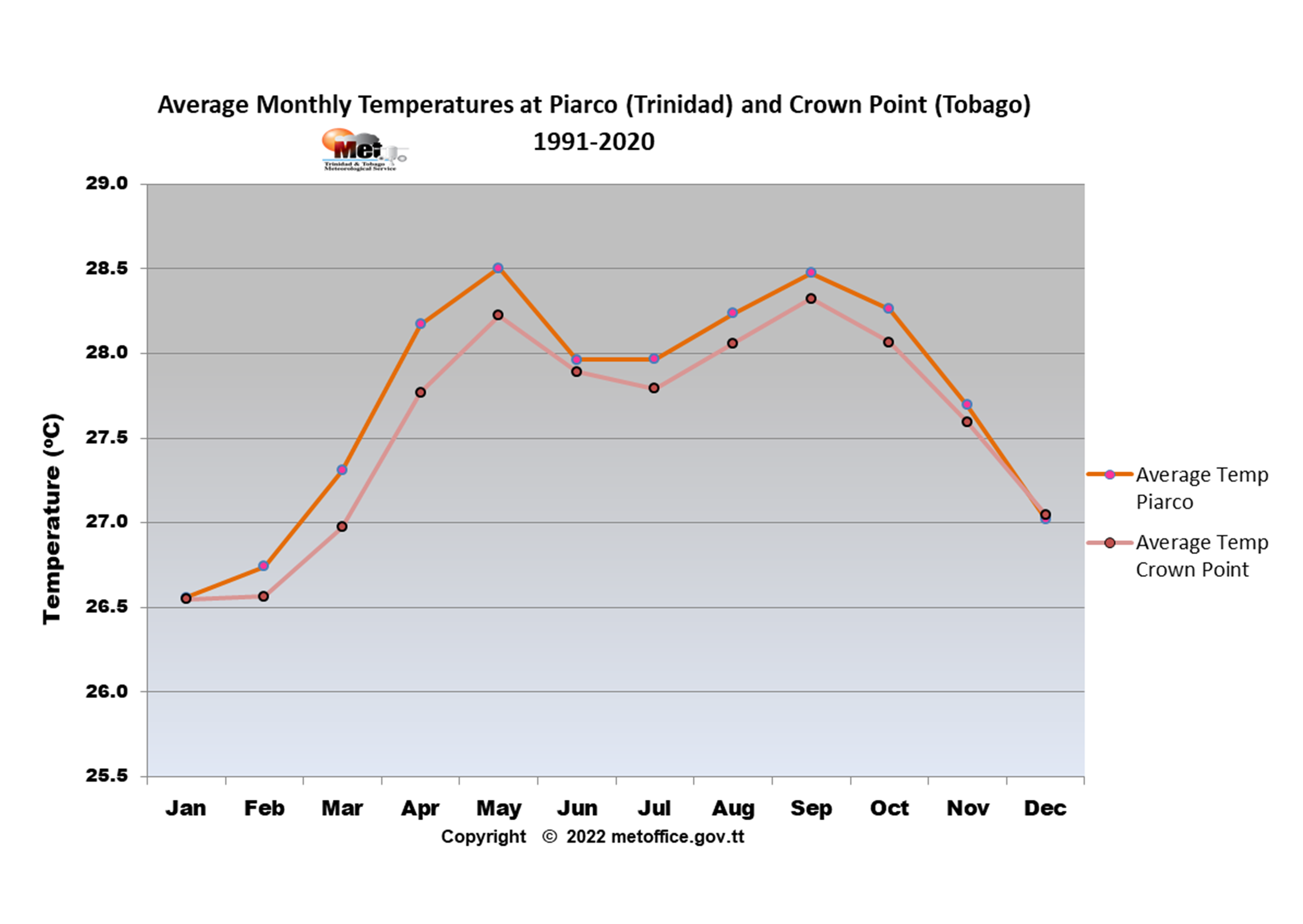

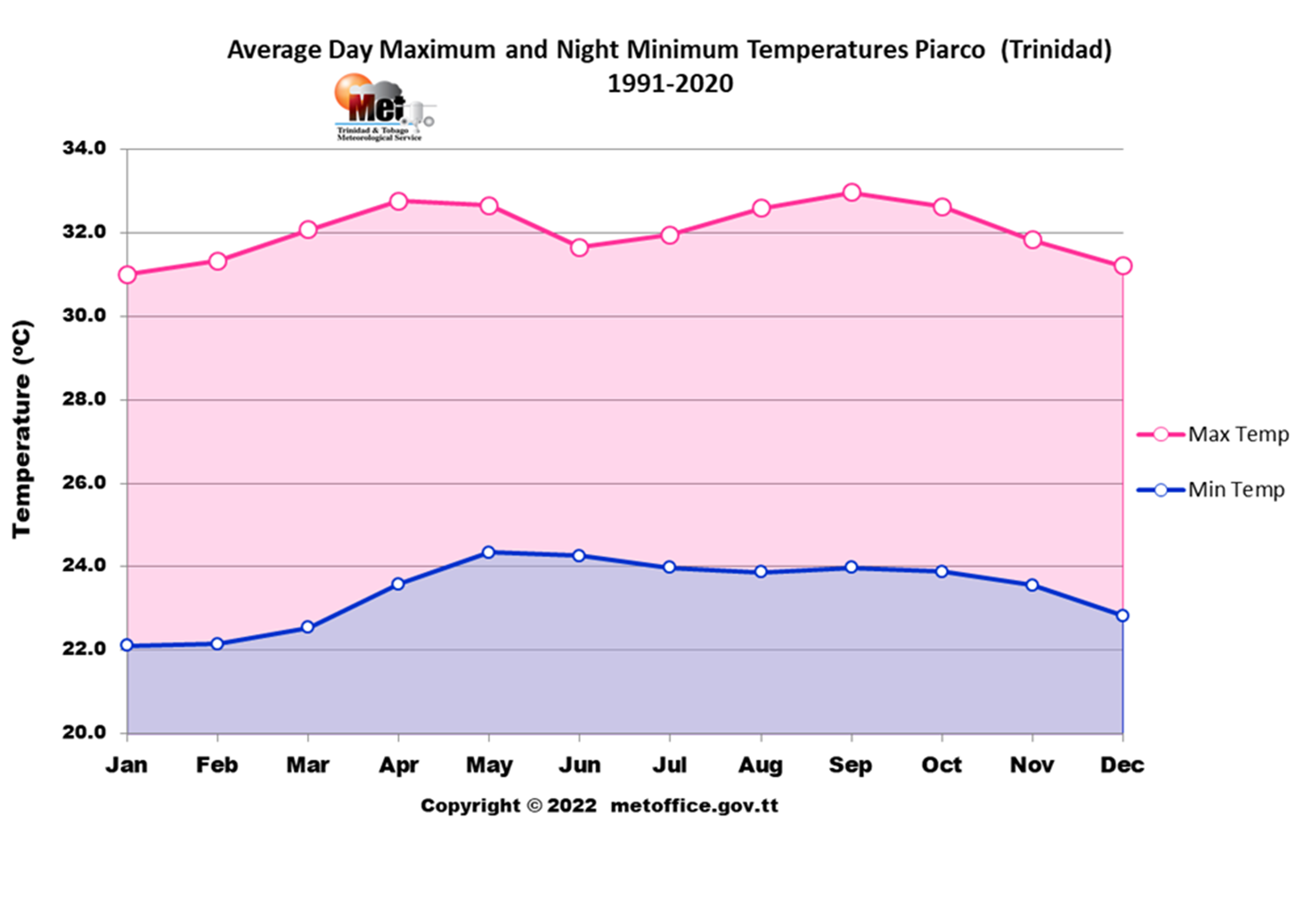

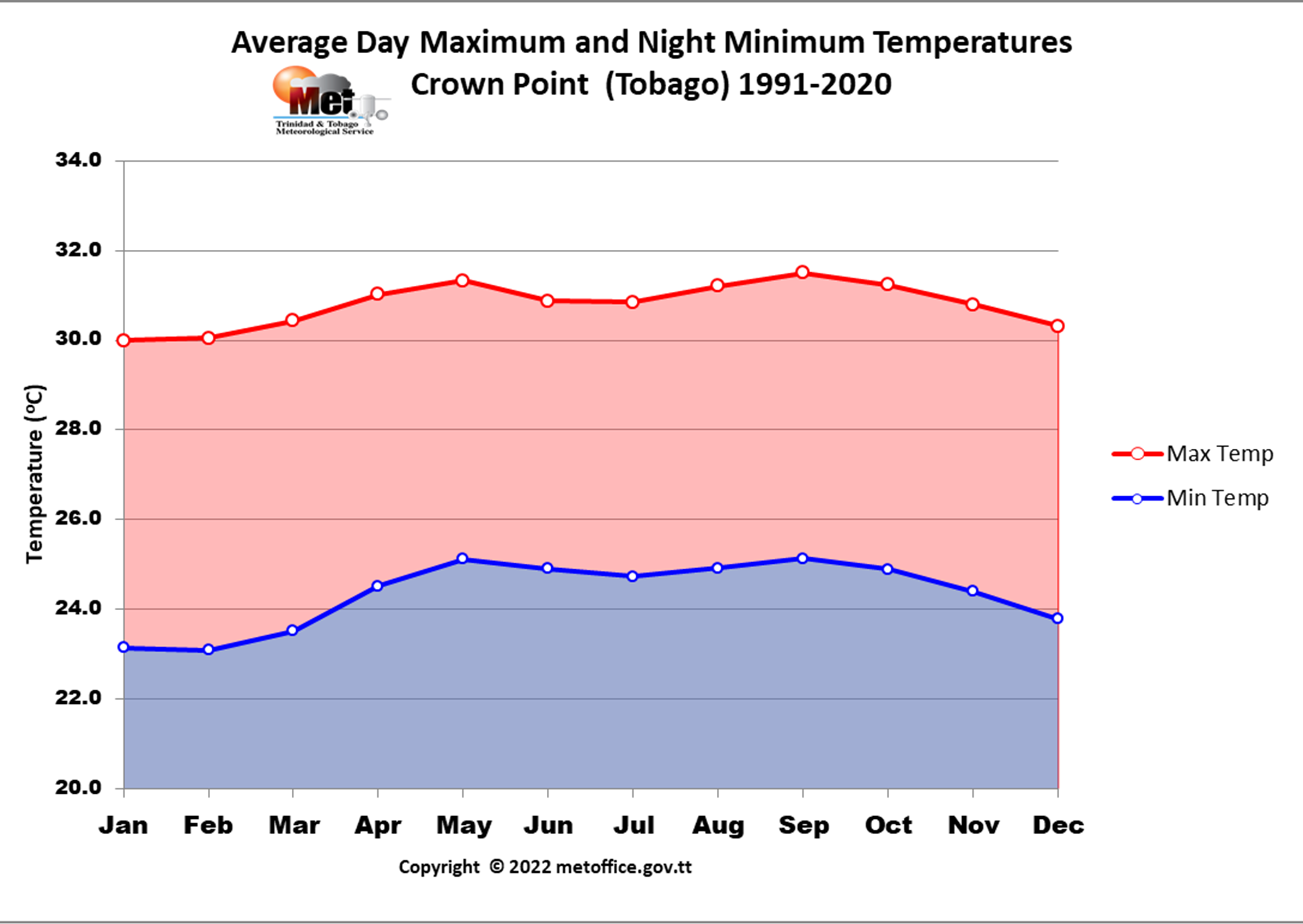

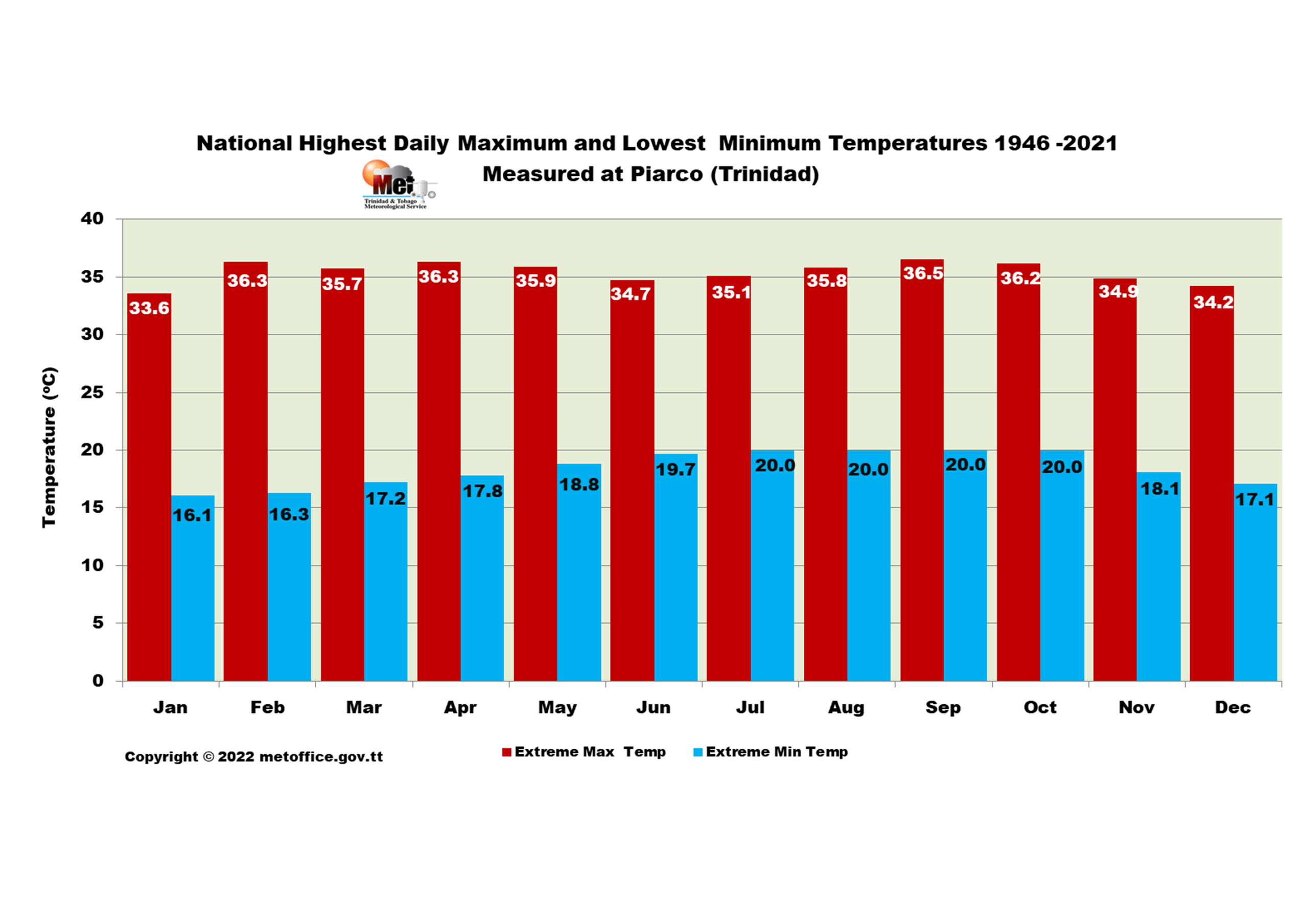

The national temperature, rainfall, sunshine and dust haze conditions for Trinidad and Tobago from 1946 to 2021 are shown on this page in graphical and tabular formats. The purpose of the graphs and tables is to highlight the long-term averages and extremes of Trinidad and Tobago climate record.

The long-term average, known as the climatological normal, shows the latest set of 30-year averages, covering the period 1991-2020, for the reference climatological stations at Piarco, Trinidad and Crown Point, Tobago.

| Copyright and contact information |

|---|

Please note that the copyright for any data supplied by the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service is held in the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago and the user shall give acknowledgement of the source in reference to the data, graphic and information. The users shall not reproduce (electronically or otherwise), modify or supply these graphic, data, or information as if it were their own.

| Averages |

|---|

These graphs show the average annual, seasonal and monthly temperature, rainfall distribution, extreme values and ranking across Trinidad and Tobago. These values can be used to provide an estimate of what is most likely to happen. The averages for various annual, seasonal and monthly time periods are calculated over the period 1991 to 2020.

| Temperature Climatology |

|---|

| Long-term Average Monthly Temperatures (°C) | Long-Term Average Monthly Day-Maximum and Night-Minimum Temperatures (°C) |

|---|---|

|

|

| At the national climate reference stations located at Piarco, Trinidad and Crown Point, Tobago, for the climate reference period 1991 -2020. May and September are the warmest months in terms of daily average temperatures. February is the coolest month. | At Piarco for the climate reference period 1991-2020. In terms of daily maximum average temperatures, September is the warmest month, with an average maximum temperature of 33.0°C, followed by April with an average maximum temperature of 32.8°C. The months of May and June share average minimum night temperatures of 24.3°C and have the warmest nights on average. |

| Long-Term Average Monthly Day-Maximum and Night-Minimum Temperatures (°C) | National Monthly Record of Warmest Daily Maximum Temperatures and Coolest Minimum Temperatures (°C) |

|---|---|

|

|

| At Crown Point for the climate reference period 1991-2020. September is the warmest month, in terms of daily maximum average temperatures, with an average maximum temperature of 31.5°C followed by May with an average maximum temperature of 31.3°C. May and September with average minimum night temperatures of 25.1°C have the warmest nights on average. | Measured at Piarco from 1959 to 2021. The warmest maximum daily temperature recorded nationally is 36.5°C, which occurred on September 25th, 1990 at Piarco. The coolest minimum temperature is 16.1°C, which occurred on January 21st and 30th, 1964 at Piarco. |

| Highest and Lowest Extreme Daily Maximum and Minimum Temperatures (°C) |

|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Nov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Temp | 33.6 | 36.3 | 35.7 | 36.3 | 35.9 | 34.7 | 35.1 | 35.8 | 36.5 | 36.2 | 34.9 | 34.2 |

| Date | 17/2012 | 25/2010 | 8/2010 | 16/2016 | 11/2010 | 22/2010 04/1999 | 29/1999 | 23/2017 | 25/1990 | 17/2016 19/2016 | 8/2008 | 21/2010 |

| Extreme Min Temp | 16.1 | 16.3 | 17.2 | 17.8 | 18.8 | 19.7 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 18.1 | 17.1 |

| Date | 21/1964 30/1964 | 24/1979 | 2/1962 | 15/1976 | 4/1967 | 23/1971 | 9/1961 | 7/1965 15/1965 | 2/1974 | 15/1976 | 17/1970 | 29/1975 |

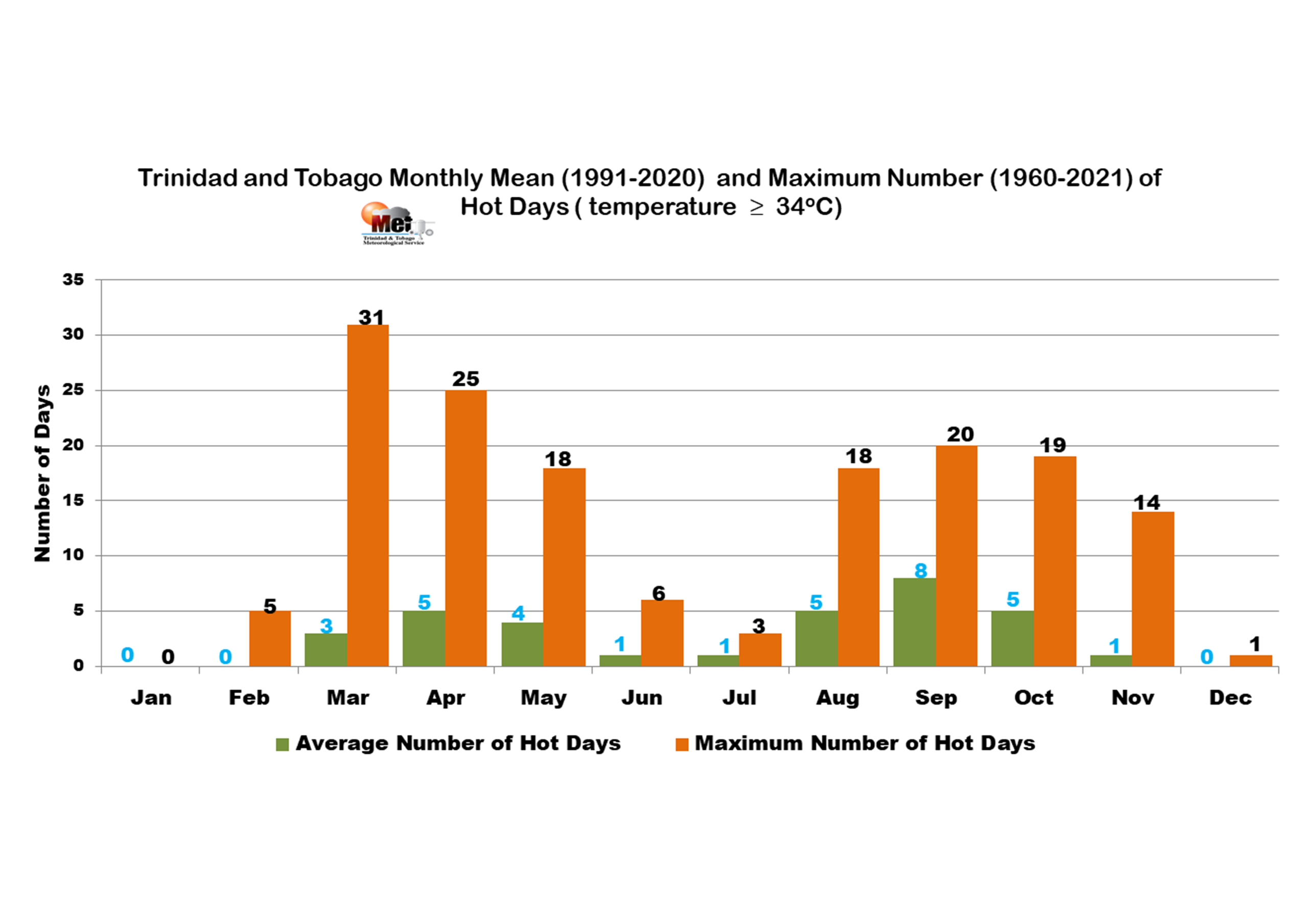

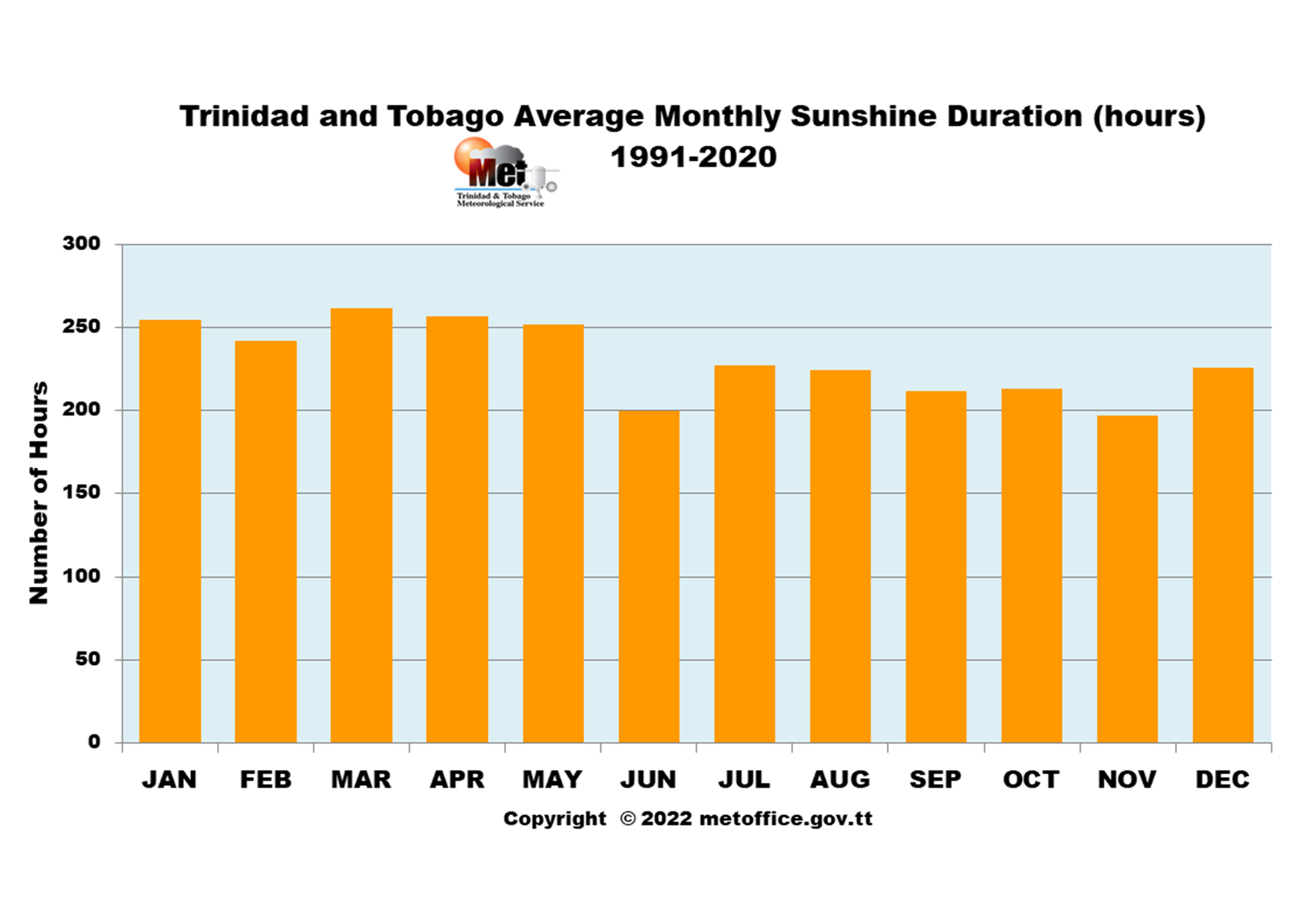

| Local Heat Season in Trinidad and Tobago (Hot Days) | Average Annual Sunshine Totals (Hours) |

|---|---|

|

|

| The local heat season in Trinidad and Tobago is defined by the period with the highest frequency of hot days in the record. Hot days are days when the maximum temperature reach or exceed the 95th percentile, which is 34.0°C. Typically, Trinidad and Tobago heat season occurs from March to October, with the hottest weather and the most excessive heat occurring during April to May and August to October, which are the peaks of the local heat season. | Trinidad and Tobago average (1991-2020) annual sunshine total is 2766 hours. On average, the sunniest month is March, with a monthly average of 261.5 sunshine hours, followed by April with 256.6 hours. November is the least sunny month, with average sunshine hours of 197.2 hours. The sunniest month on record is March 2010 with 319.5 sunshine hours. The least sunny month on record is June 1982 with 104 sunshine hours. |

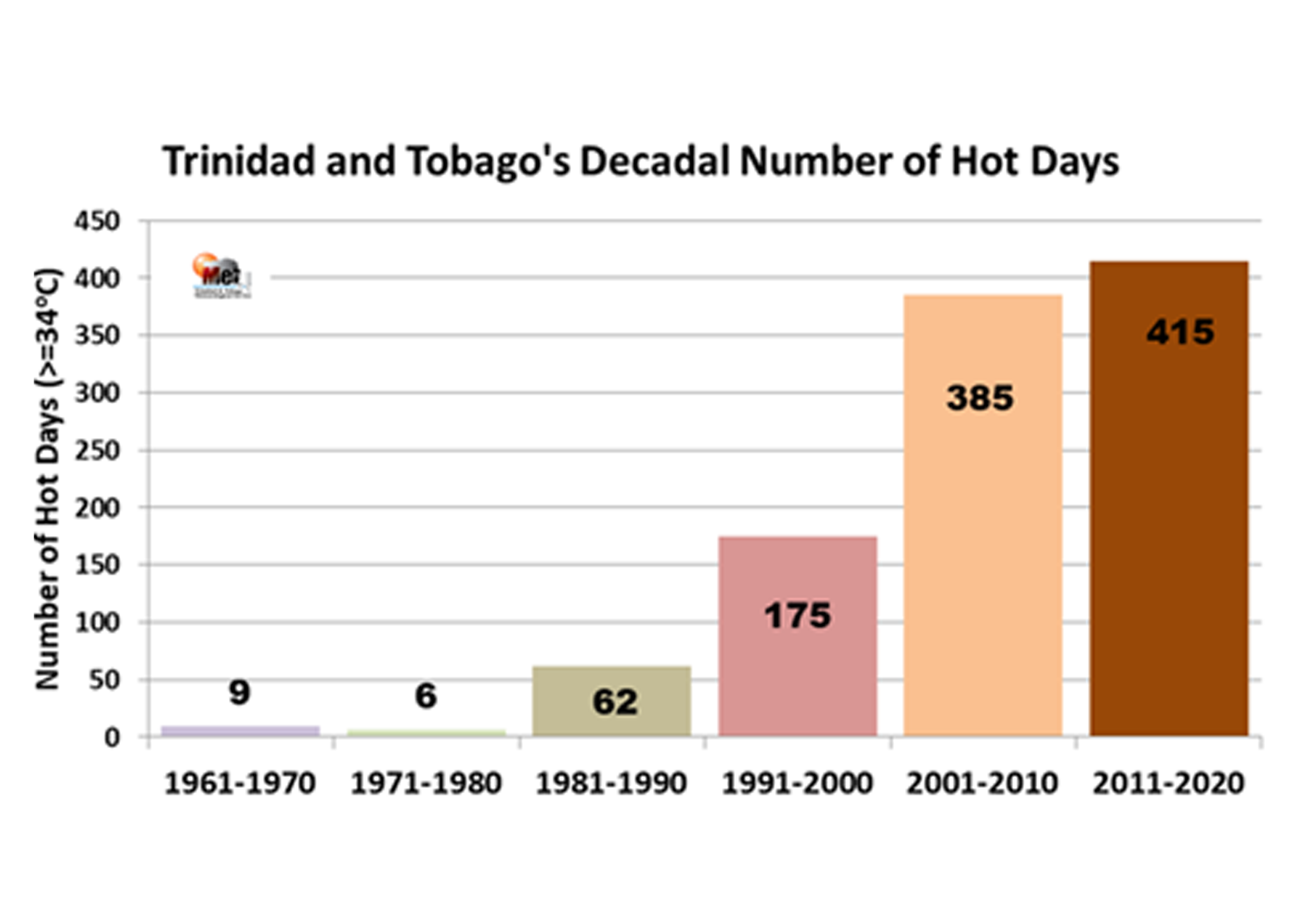

| Change in Trinidad and Tobago Decadal Average Daily Maximum Temperature (ºC) Between 1951 and 2020 | Changes in Decadal Hot Days in Trinidad and Tobago from 1960-to 2020 |

|---|---|

|

|

| Decadal average daily maximum temperatures at Piarco, Trinidad have risen by about 1.1 ºC. | The graphic shows the decadal trend in hot days in Trinidad and Tobago from 1960-to 2020. A hot day is a day when the maximum temperature equals or exceeds 34°C (the 95th percentile). Hot days in the last decade have occurred more than twice the amount of hot days in the 1990s. |

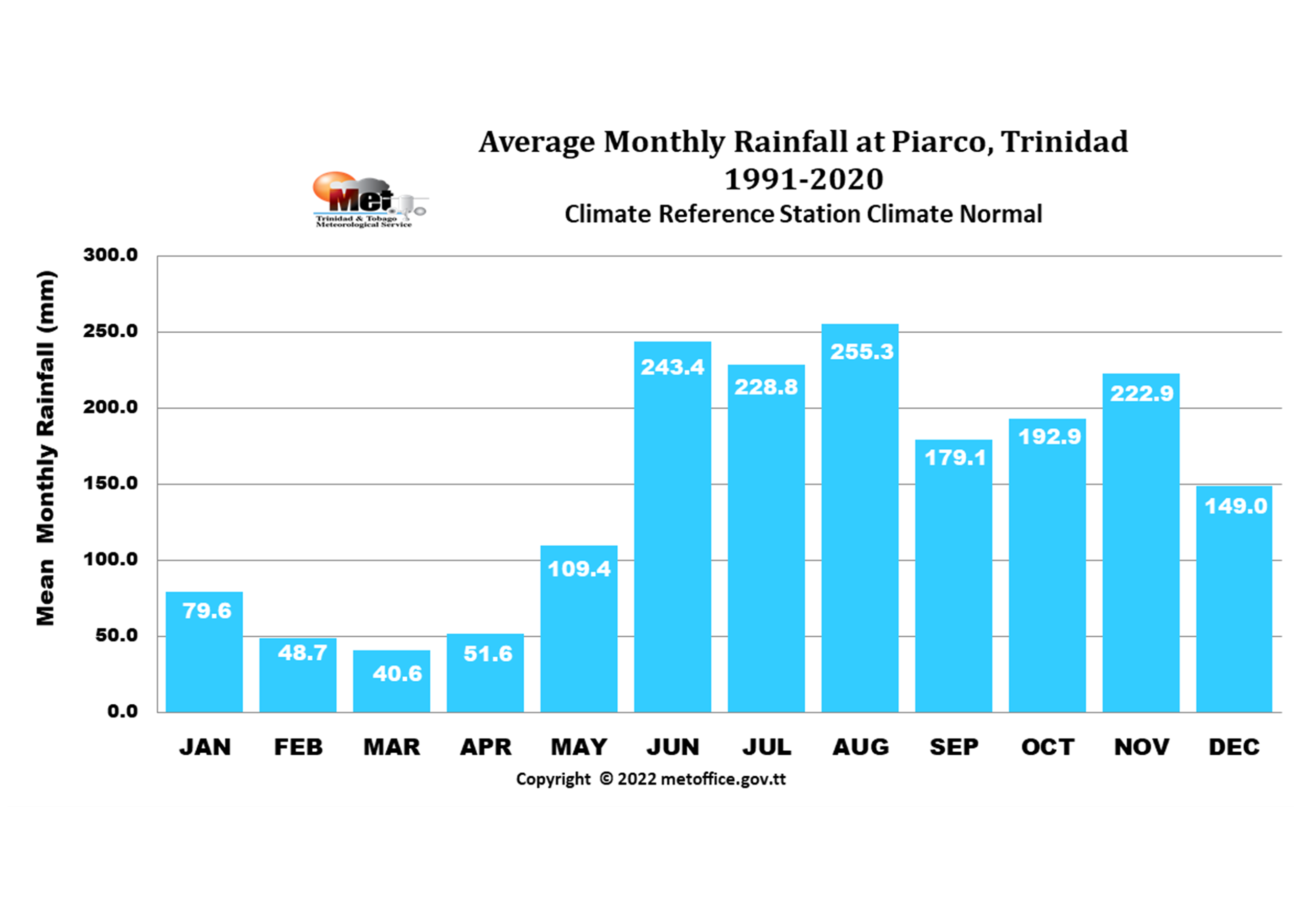

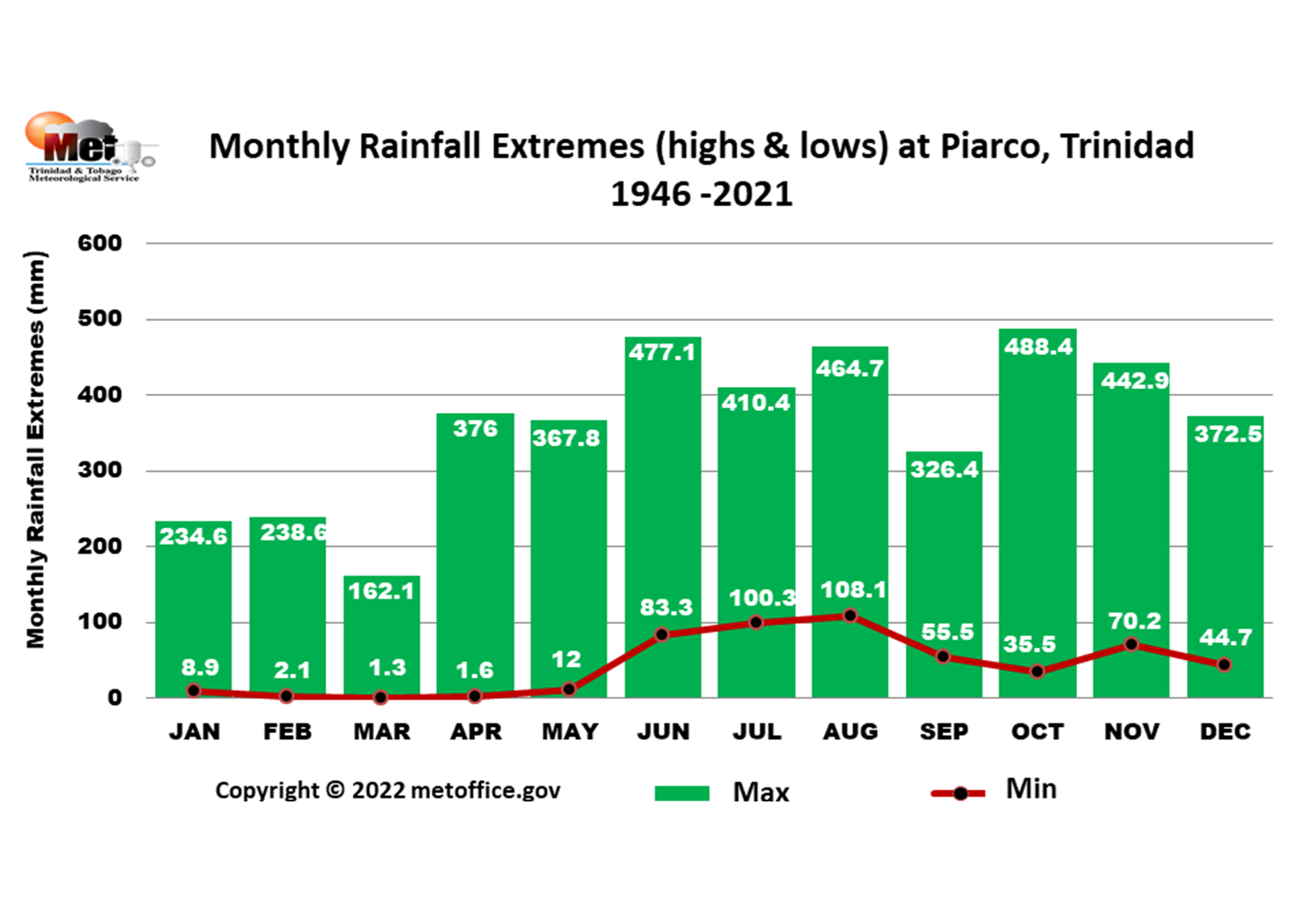

| Long-Term Average Monthly Rainfall Totals (mm) | Monthly Extreme Rainfall Records at Piarco (mm) |

|---|---|

|

|

| At Piarco for the climate reference period 1991-2020. August is the wettest month, with an average monthly rainfall total of 255.3 mm, followed by June and July. The month of September is usually the driest month of the wet season with 179.1 mm. Sometimes there is a short dry spell in September across the entire country, which may possibly last for one to two weeks or even longer as seen in some years. The driest month of the year is March, with an average of 40.6 mm of rainfall. | The month of October (1988) with 488.4 mm produced the highest monthly rainfall total on record at Piarco between 1946 and 2021. The month of March (1966) with 1.3 mm has produced the lowest monthly rainfall totals |

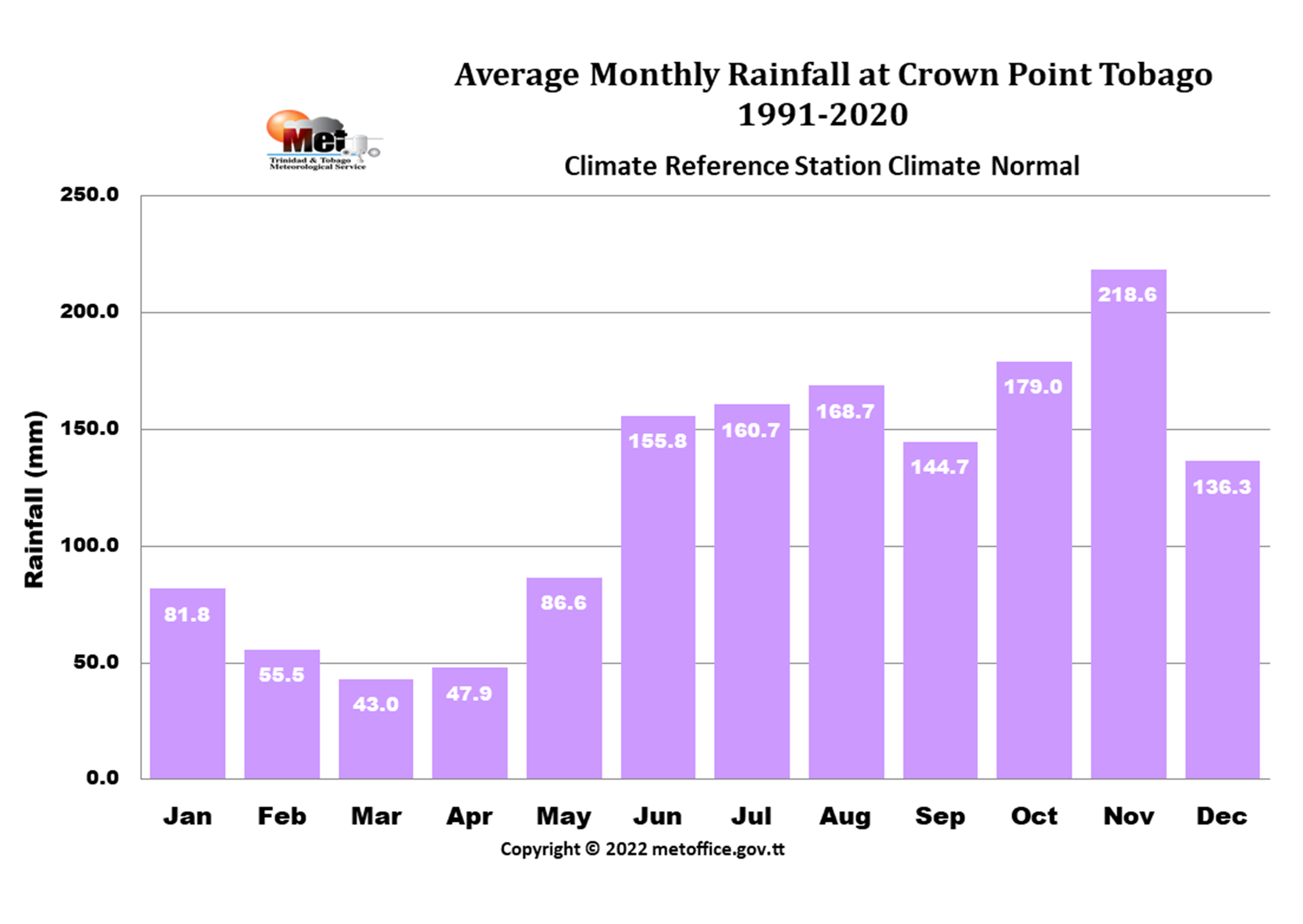

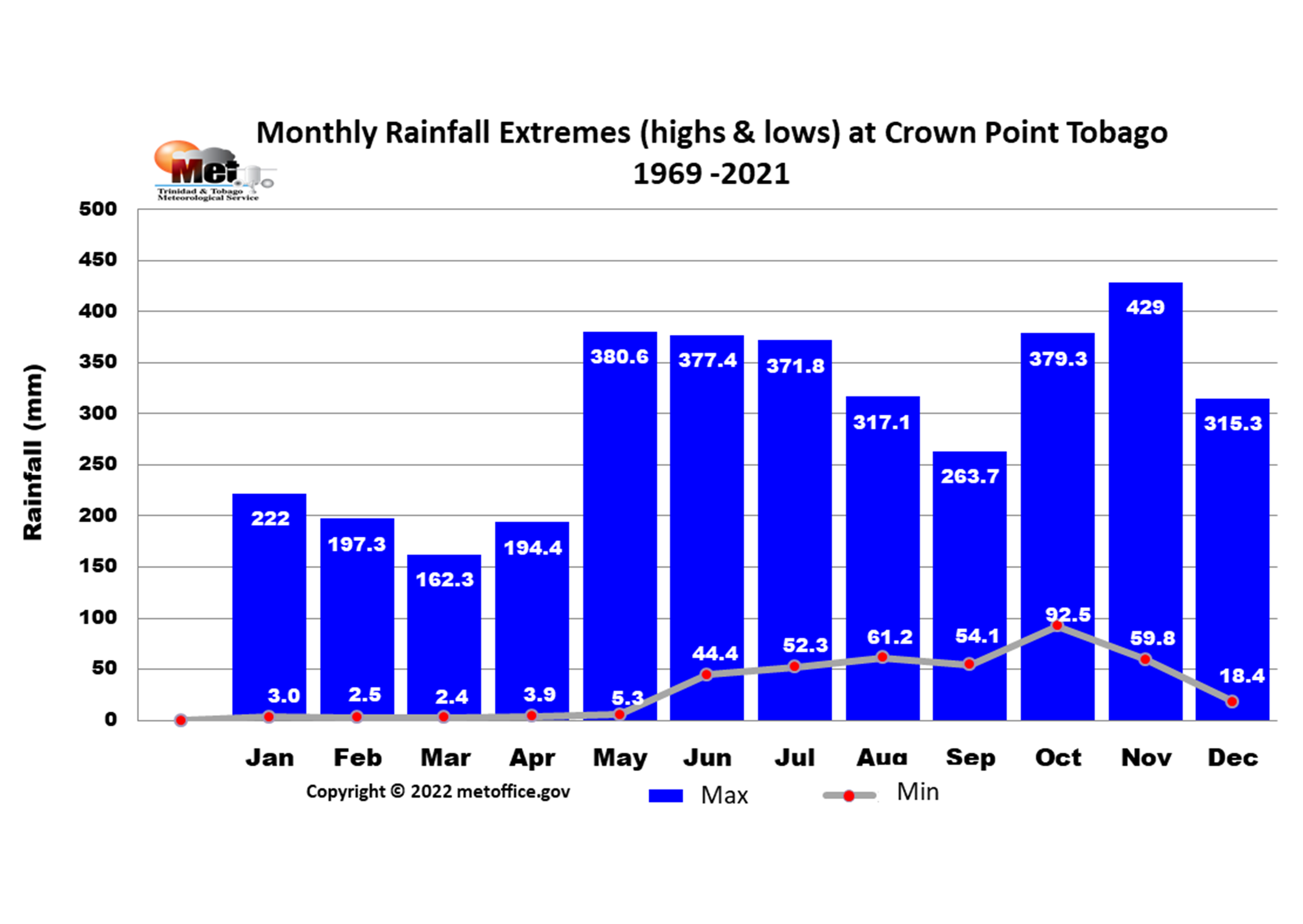

| Long-Term Average Monthly Rainfall Totals (mm) | Monthly Extreme Rainfall Records at Crown Point (mm) |

|---|---|

|

|

| At Crown Point for the climate reference period 1991-2020 November is the wettest month, with an average monthly rainfall total of 218.6 mm, followed by October with 179.0mm. The month of December is usually the driest month of the wet season, with an average rainfall total of 136.3 mm. March is usually the driest month of the year, with an average of 43.0 mm. | The month of November (2004) with 429.0 mm produced the highest monthly rainfall total on record at Crown Point between 1971 and 2021. Whereas, the month of March (1992) with 2.4 mm produced the lowest monthly rainfall total on record. |

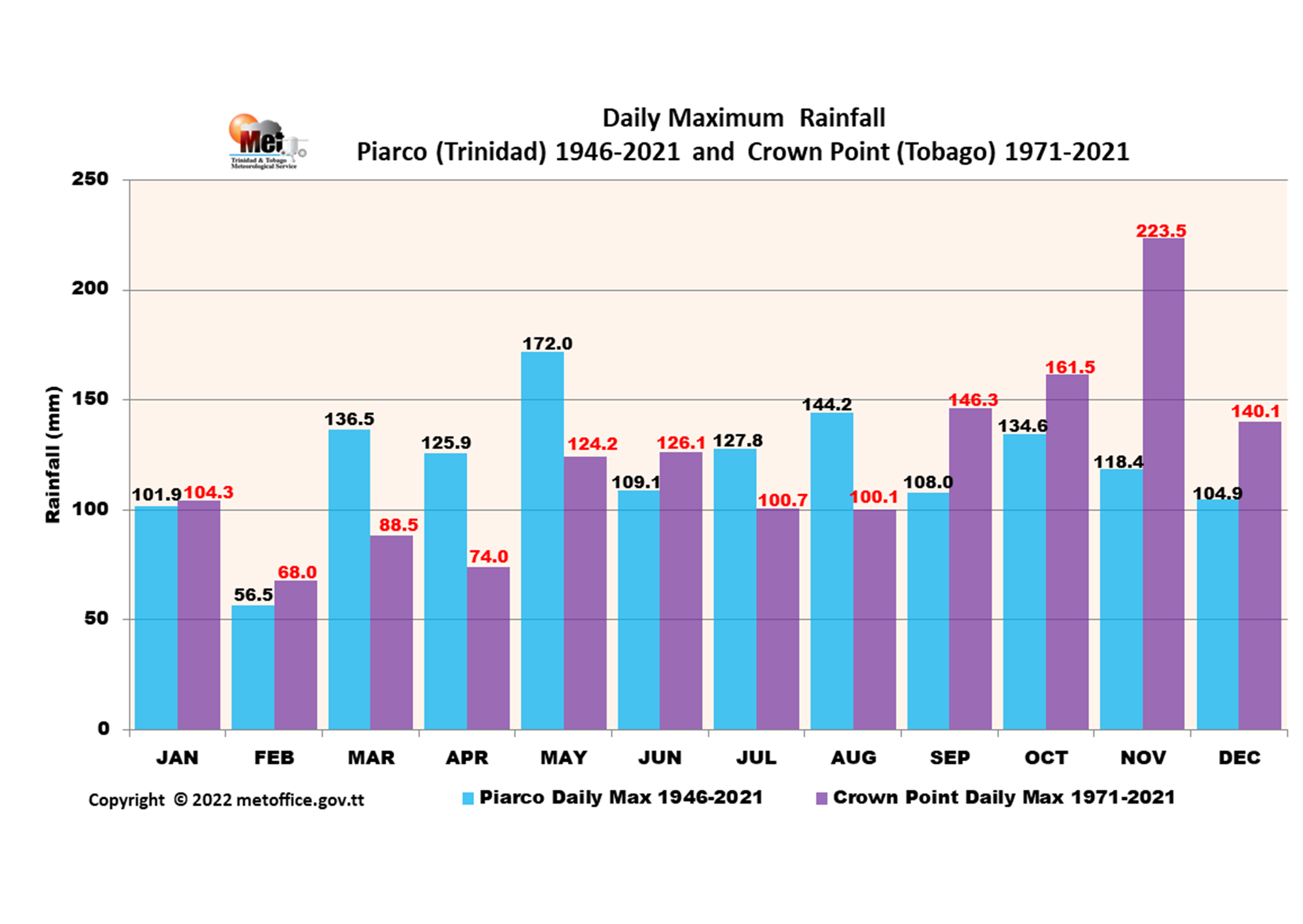

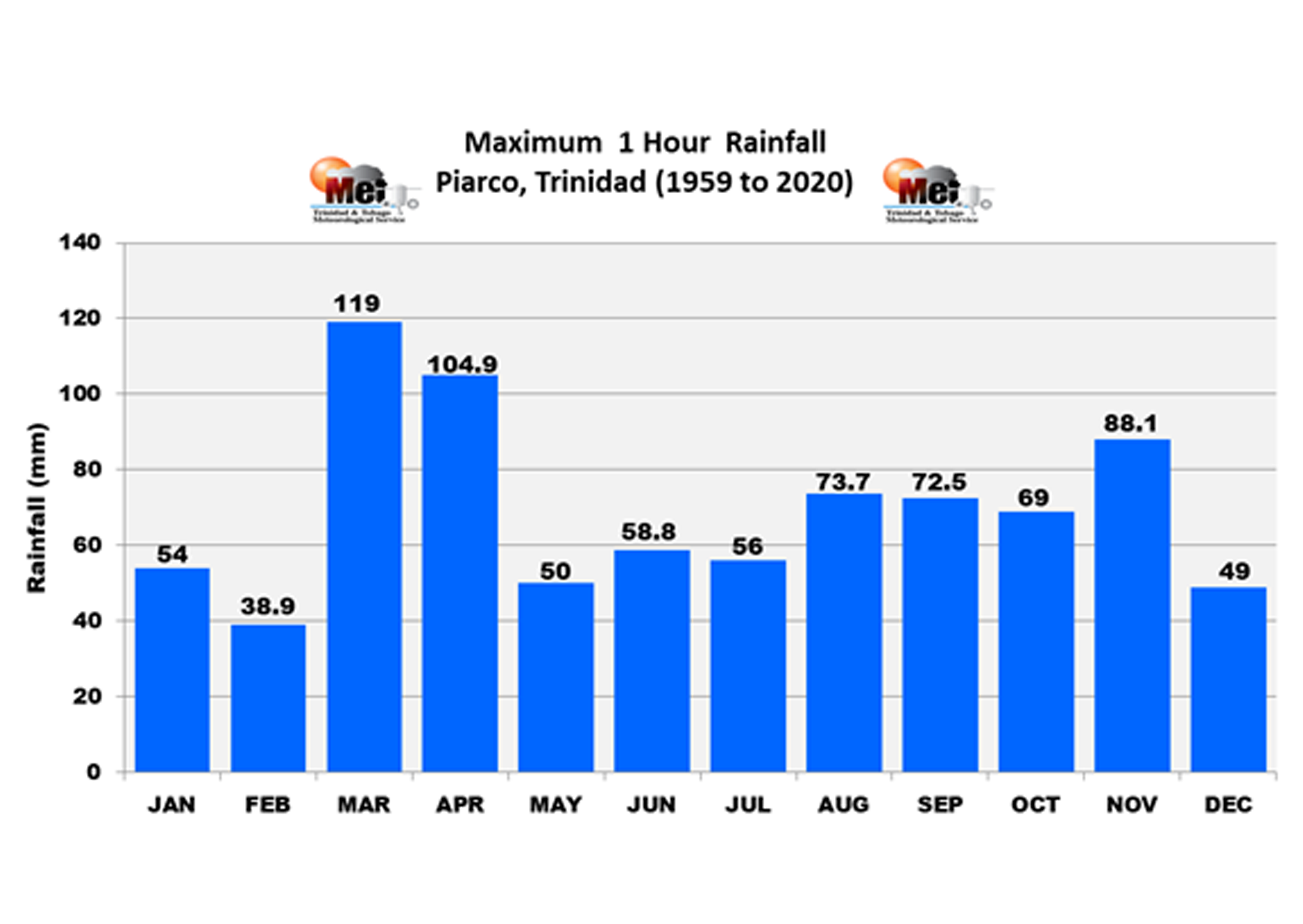

| Record of Highest Daily Maximum Rainfall (mm) | Record of Maximum Rainfall (mm) in 1 Hour Recorded at Piarco 1959 to 2020 |

|---|---|

|

|

| Maximum 24-hour rainfall at the monthly scale for Piarco and Crown Point for the periods 1946-2021 and 1971-2021 respectively. The highest 24-hour rainfall measured at Piarco is 172.0mm, which occurred on May 25th 2010. March which is usually the driest month, produced the 3rd highest 24-hour rainfall at Piarco. This occurred on March 04, 2018. At Crown Point, the highest 24-hour rainfall measured is 223.5mm, which occurred on November 12th, 2004. | The most rainfall in one (1) hour recorded at Piarco from 1946 to 2020 on the monthly scale is shown. The month of March, which is usually the driest month of the year has the record, which occurred on March 4th, 2018, followed by April, which occurred on April 22nd, 1973. |

| Record of Maximum and Average Number of Thunderstorm Days Observed at Piarco 1959 to 2020 |

|---|

|

| Monthly maximum numbers of thunderstorm days are shown along with the average number of thunderstorm days. Historically August has the record for the most days with thunderstorms while on average; September tends to get the most number of thunderstorm days in Trinidad and Tobago. |

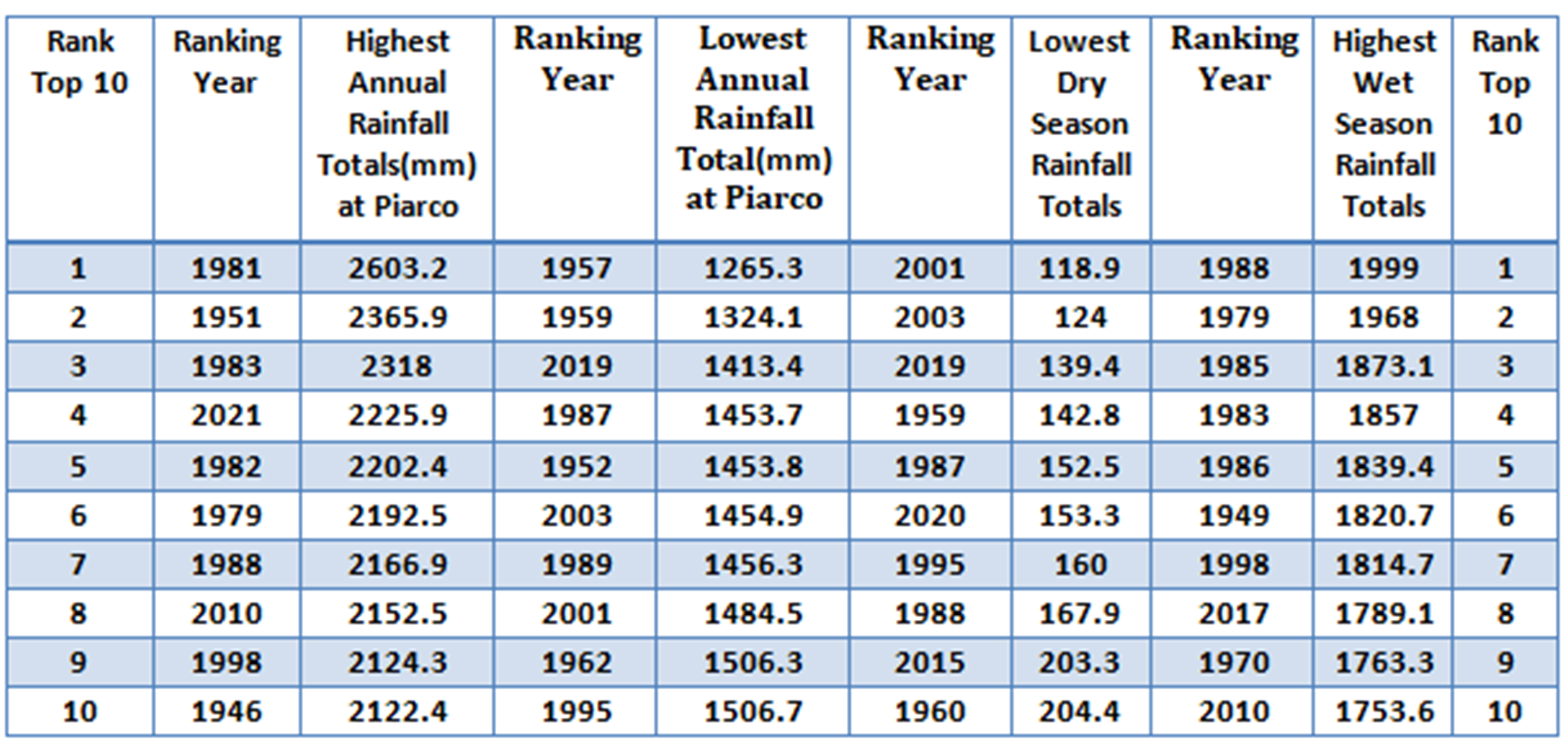

| Top 10 Ranked Highest and Lowest Annual Rainfall Totals, Lowest Dry Season Totals and Highest Wet Season Rainfall Totals at Piarco |

|---|

|

| The table on this page displays the top ten highest and lowest annual, wet and dry-seasons rainfall records at Piarco, Trinidad. |

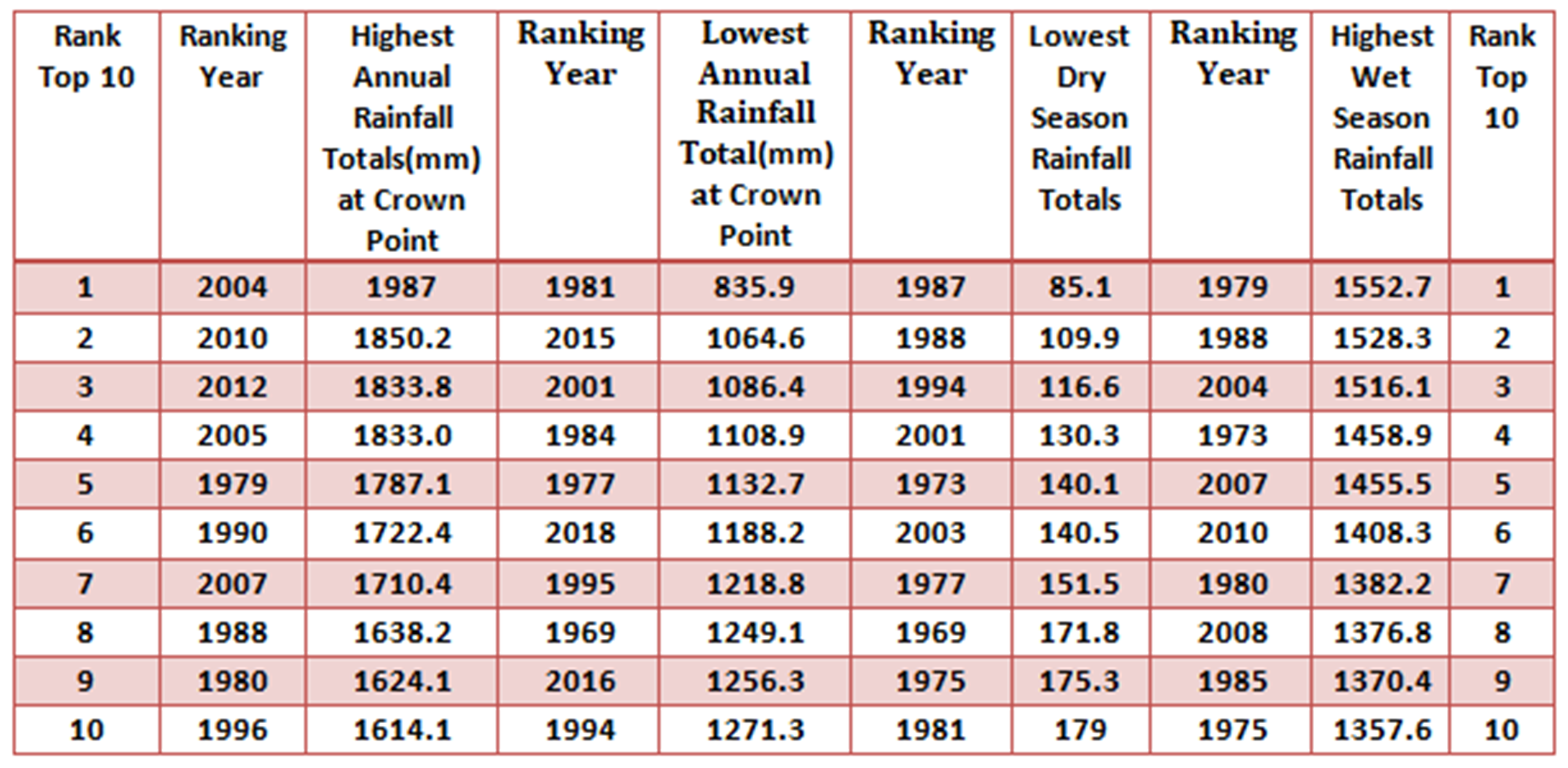

| Top 10 Ranked Highest and Lowest Annual Rainfall Totals, Lowest Dry Season Totals and Highest Wet Season Rainfall Totals at Crown Point |

|---|

|

| The table on this page displays the top ten highest and lowest annual, wet and dry-seasons rainfall records at Crown Point, Tobago. |

| HAIL EVENTS |

|---|

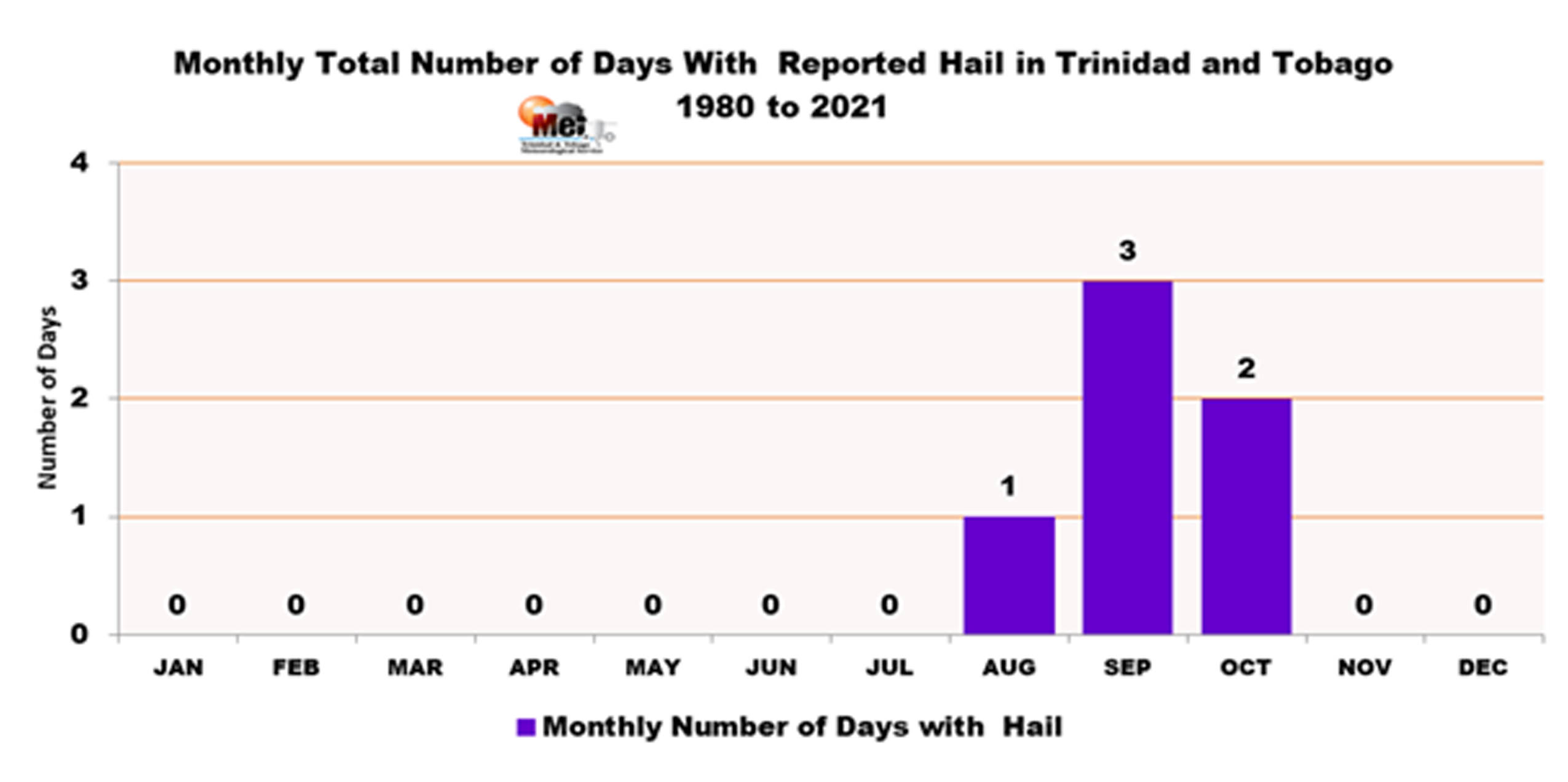

| Hail Reports in Trinidad and Tobago by Month, Since 1980 |

|---|

| This hail climatology report was obtained from the Meteorological Services Division (MSD) records. It will assist with understanding when a hail event is most likely to occur and when a rare event occurs. There have been 6 reports of hail occurrences that have been verified by the MSD in Trinidad and Tobago since 1980. The number of hail reports rose steadily over the years, doubling from 1 in the 1980s to 2 in the 1990s and 3 in the 2020s. The last two years had 3 reports, 2 in 2020 and 1 in 2021. N.B. These are events that the Meteorological Services Division has in its records. There may have been other events reported but were not verified or recorded by the MSD. |

| Trinidad and Tobago Record of Hail Events |

|---|

| Date | Location | Time | Maximum Day Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 29, 1985 | Diego Martin Valley | After Lunch | 32.0ºC |

| September 2, 1990 | Southern Cunupia (about 3 km south of Piarco) | After Lunch | 33.7ºC |

| August 12, 1996 | La Romain, San Fernando, Penal | After Lunch | 33.5ºC |

| September 08, 2020 | Carlsen Field, Central, Trinidad | 2:45 pm to 3:15 pm | 33.8ºC |

| October 17, 2020 | Piarco, North Terminal | 2:00 pm | 33.1ºC |

| September 27, 2021 | Tacarigua, Trincity, Arouca | 1:20 pm to 1:40 pm | 33.8ºC |

| Monthly Total Days with Hail Reported in Trinidad and Tobago (1980-2021) |

|---|

|

| Not surprisingly, 50% of the hail reports in Trinidad and Tobago occurred in September with the remaining 50% occurring over August and October. These three months are both the warmest months of the wet season and the months with the lightest winds on average. September is the warmest month on average in the year and also the record holder for the hottest day on record. |

| Dust Haze Climatology |

|---|

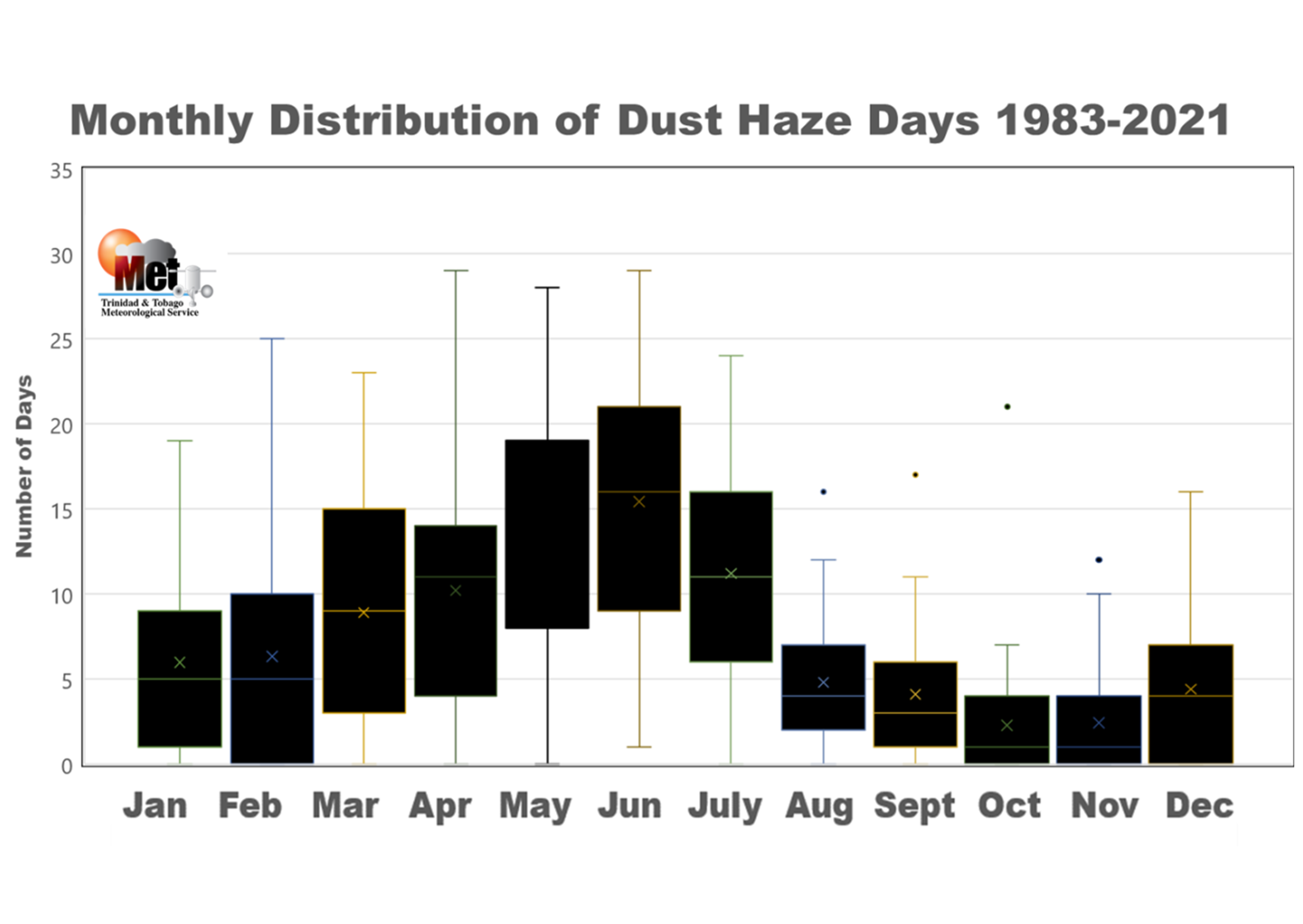

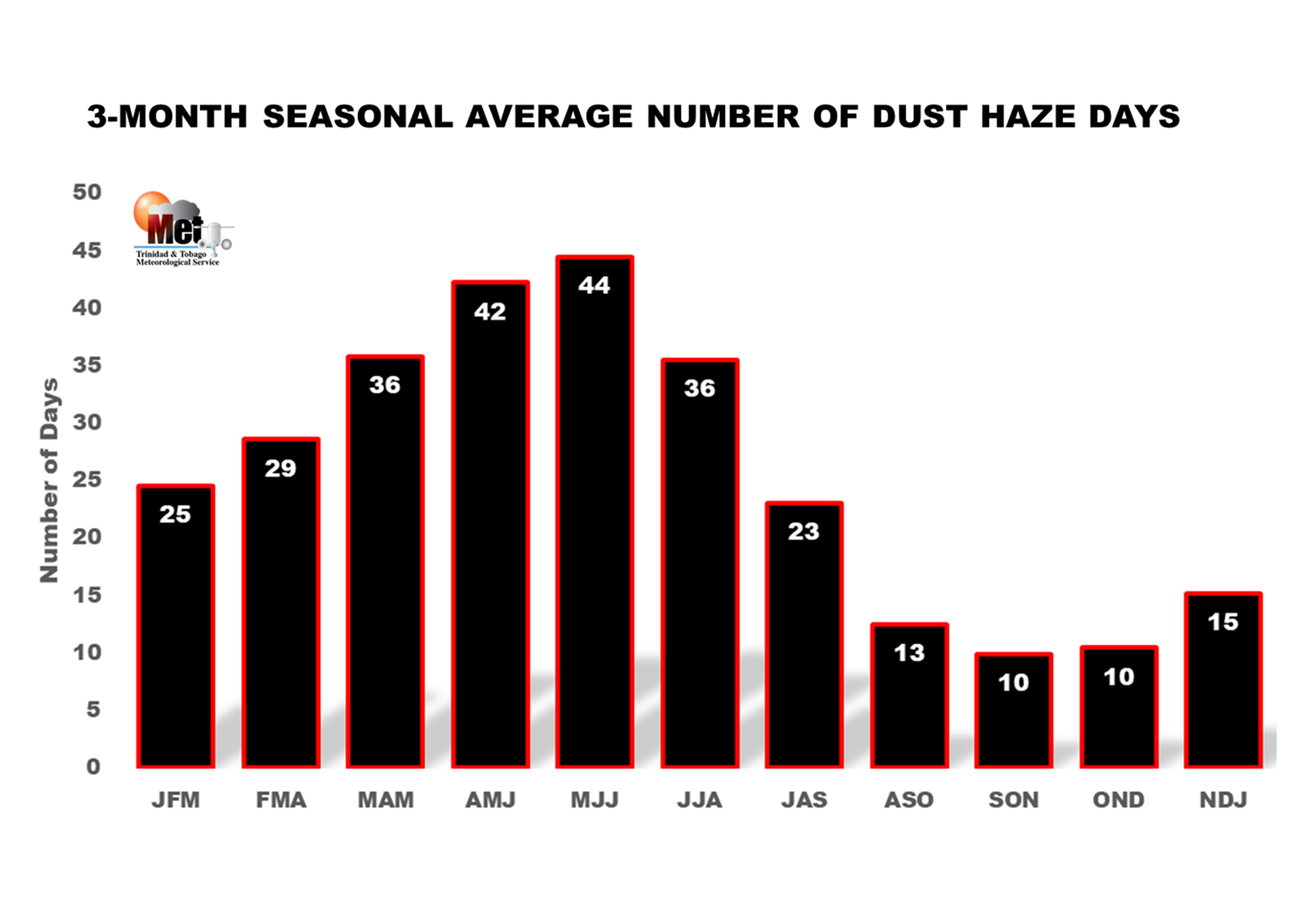

|

|

| This graphic shows the monthly distribution of dust haze days for Trinidad and Tobago between 1983 and 2021. Monthly average Saharan dust haze days and frequency varies significantly, but the proportion of dust haze days is highest in June followed by May and July. This period is is the peak of the local Saharan Dust Haze season. | Long-term averages of the number of dust haze days for 3-month seasons are shown in this graph. The peak of the local Saharan Dust Haze season is May-June-July, which on average gets 44 dust haze days. |

| Trinidad and Tobago Monthly Average of Daily Wind Speeds |

|---|

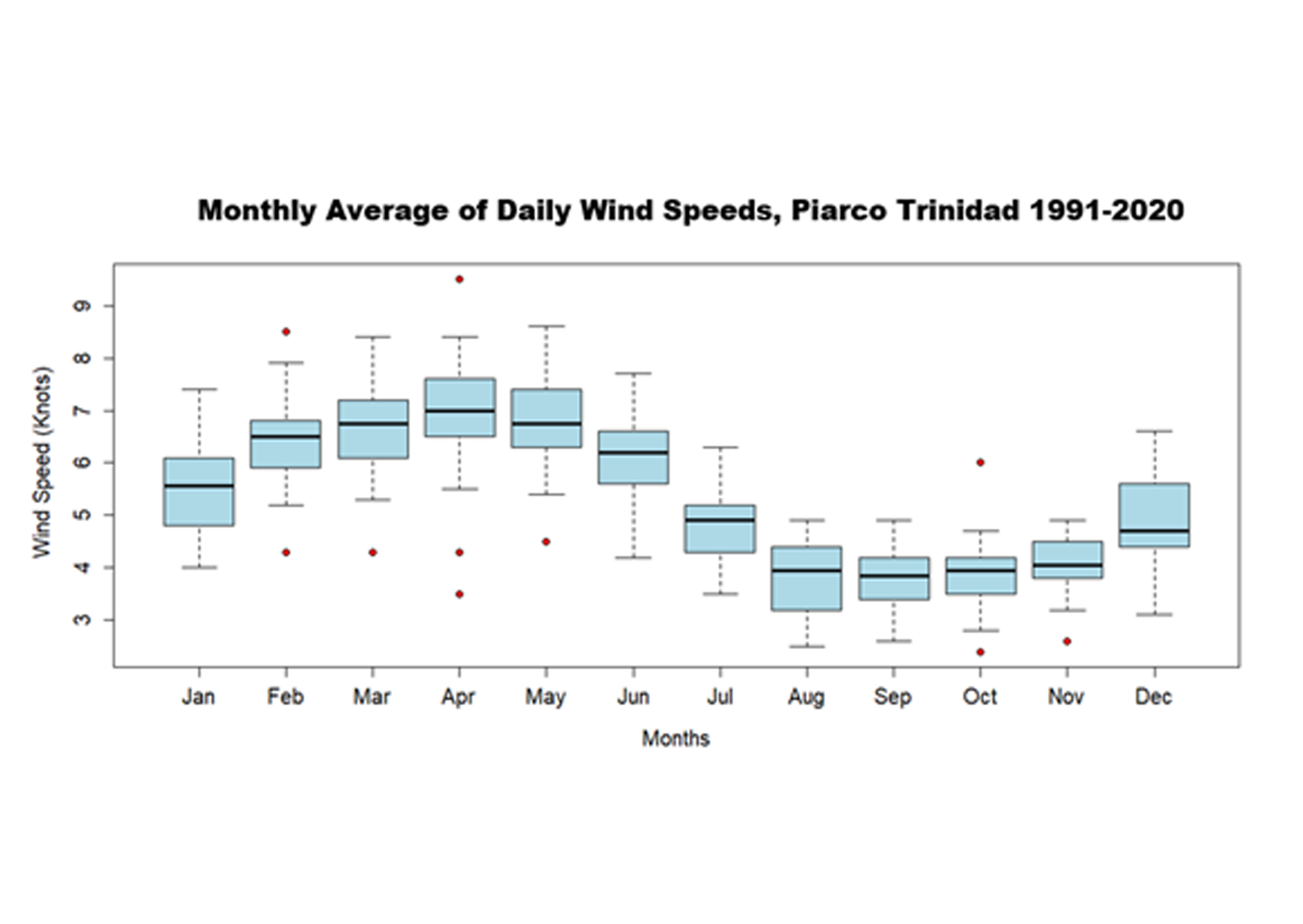

| Monthly Average of Daily Wind Speeds | Hourly surface wind speed observations |

|---|---|

|

|

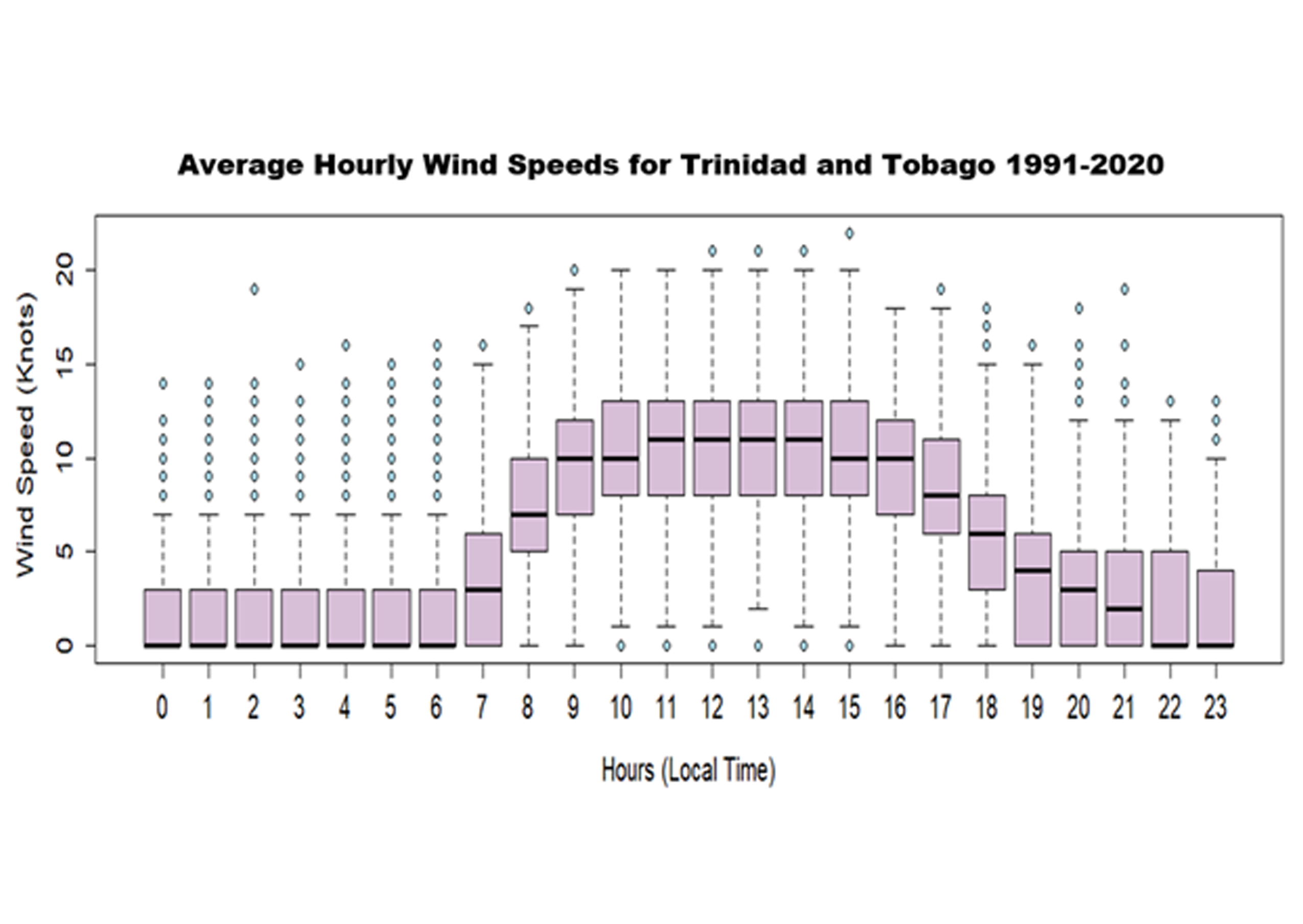

| The graphic shows the boxplot of monthly averaged surface wind speeds measured at the standard 10-meter height at the Piarco Meteorological Office over the period 1991-2020. The minimum and maximum values are indicated by the ends of the whiskers, with the mean, 25th, and 75th percentile values marked by the middle, lower and upper part of the box, respectively. On average, the month of April produces the highest monthly average wind speeds, while September tends to have the lowest average wind speeds. The dry season usually has the strongest winds with March to May having the strongest wind speeds overall. The months of August to October in the wet season usually have the lowest wind speeds. Other station records are not considered here due to length of record discrepancies. | This graphic shows a boxplot of hourly mean wind speeds for Trinidad from 1991to 2020. Hourly surface wind speed observations measured at the standard 10-meter height at the Piarco Meteorological Office over the period 1991-2020 show on average, the wind speeds to be strongest between 11:00 am and 2:00 pm and lowest between midnight and 6:00 am. Hourly extreme wind speeds can exceed 20 knots during the day. |

| Trinidad and Tobago Wind Roses |

|---|

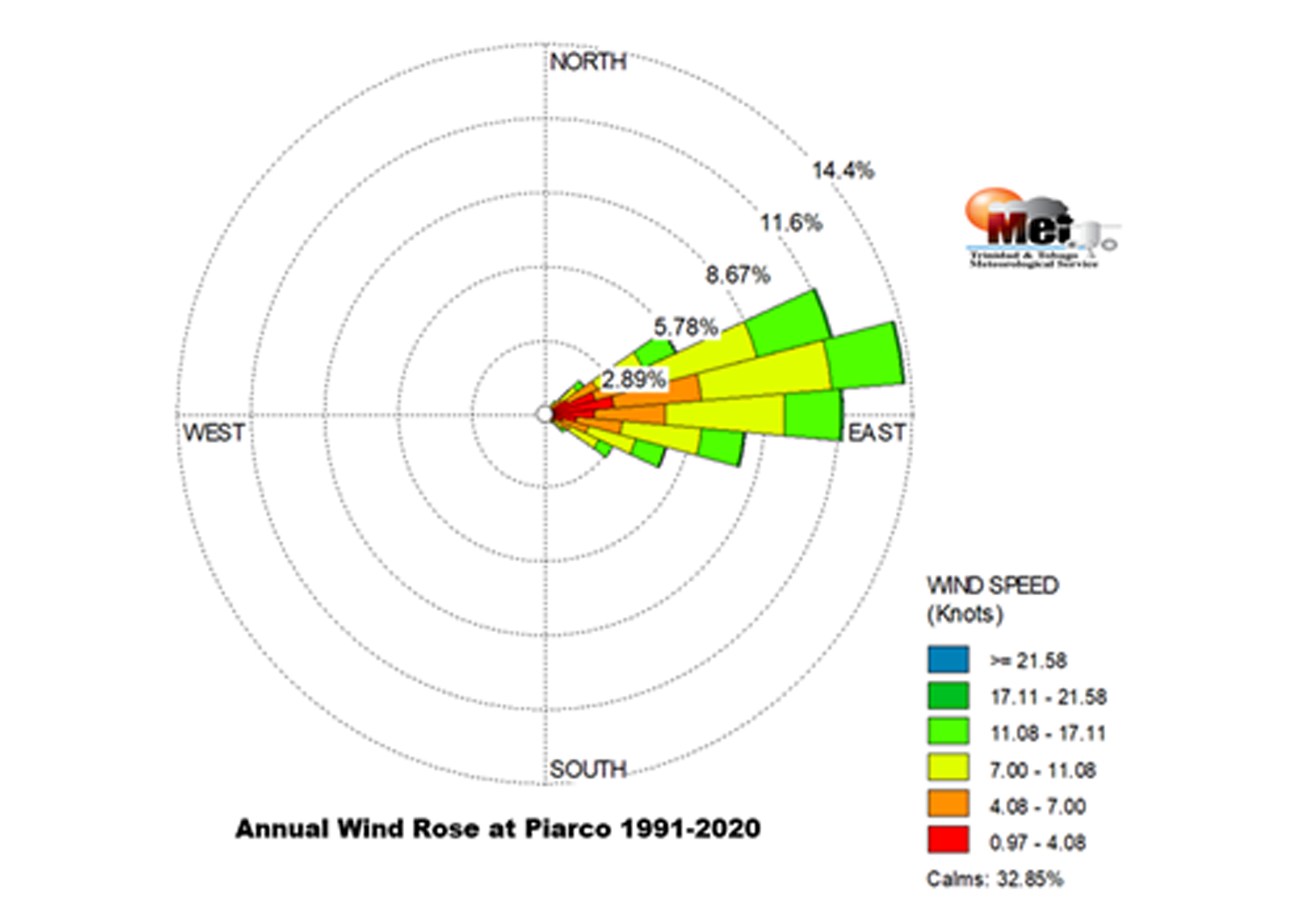

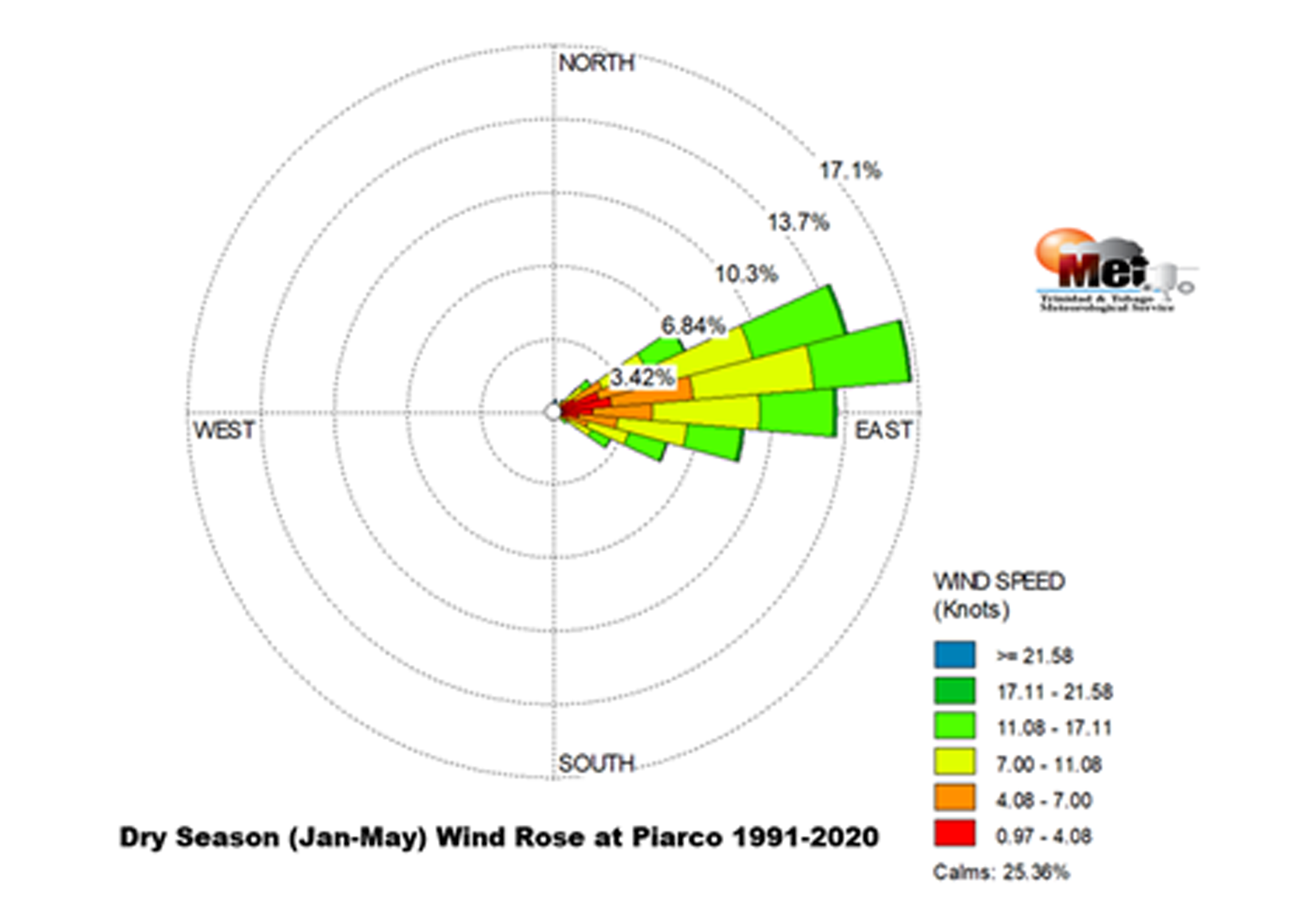

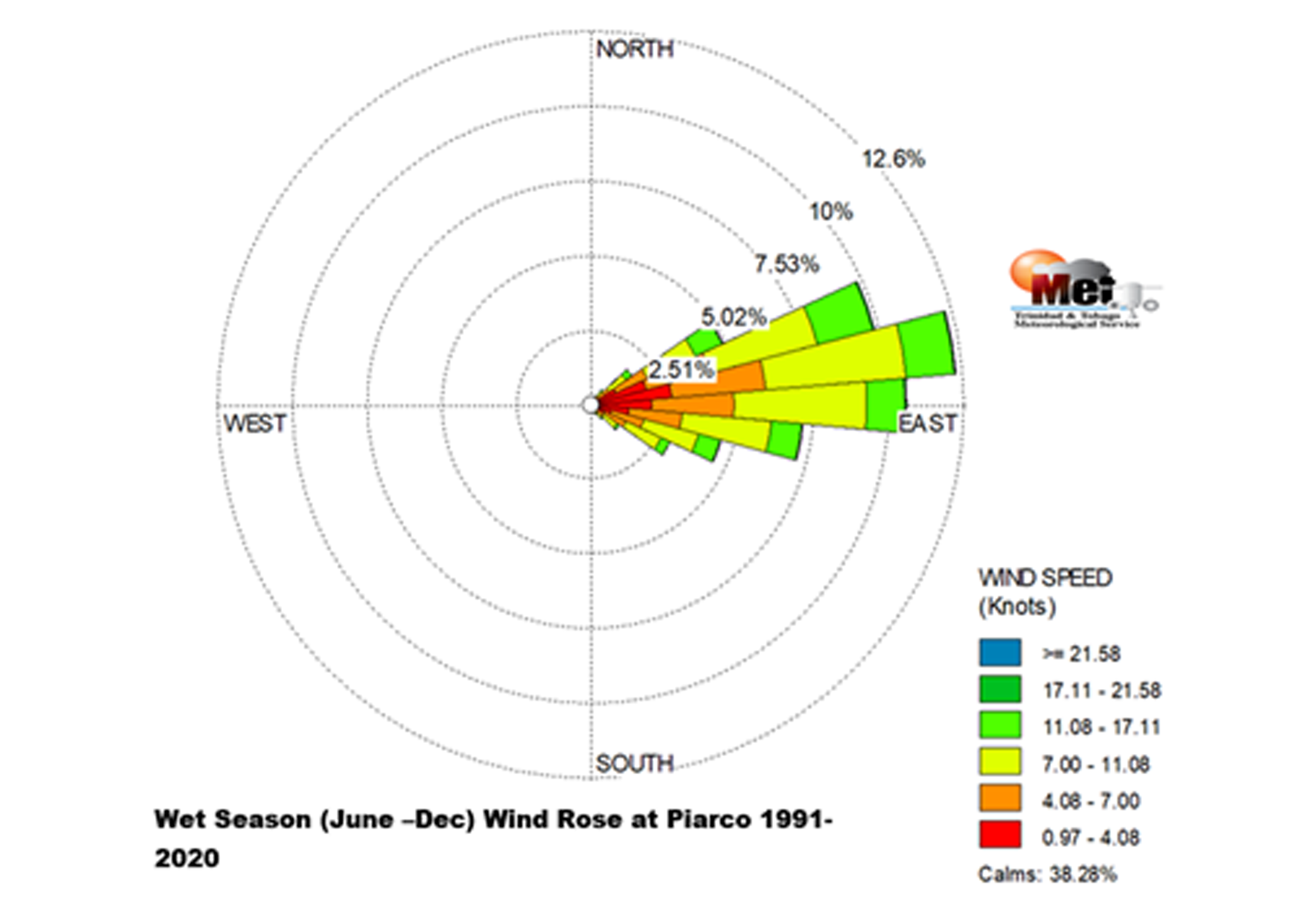

| These wind roses, graphically show the predominant wind direction and speed of the wind in Trinidad and Tobago and provide the best information regarding the percentage of time each wind direction and speed can be expected when averaged (standard climate normal 1991-2020) annually and at the dry and seasons scales in Trinidad and Tobago. |

| Annual Wind Frequency Rose 1991 -2020 | Wind frequency Rose for the Dry Seasons 1991 – 2020 | Wind frequency Rose for the Wet Seasons 1991 – 2020 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| The annual, dry and wet season wind roses show that the winds blew most frequently from east-north-east and most frequently at 7-11 knots (yellow). |

| Main Drivers of Trinidad and Tobago Climate, Rainfall and Temperature Variability |

|---|

|

| Trinidad and Tobago’s climate has high year to year and seasonal variability, with rainfall having large spatial and temporal variability, over relatively small areas. The main drivers and influencers are presented in the schematic, but these are not all the influencers. The schematic represents the main drivers of rainfall and temperature variability over Trinidad and Tobago. These include the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), North Atlantic Sub-tropical High Pressure system (NASH), North East Trades, North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO), Caribbean Low Level Jet (CLL), Tropical Upper-Tropospheric Trough (TUTT), Upper Level Trough, Shear Lines, Tropical Waves, Tropical Cyclones and Saharan Air Layer; but these are not all the influencers. |

Last updated: Friday, 03rd June 2022

The Cumulative Rainfall graph shows the total amount of rainfall accumulated over a calendar year in comparison to the cumulated rainfall of the long term average, (the climatological standard normal).

Meteorologists and Hydrologists use such graphs to help visualize how rainfall accumulates over time, whether daily, weekly, or monthly.

It is useful in climate studies for comparing rainfall patterns across different seasons or years.

This data aids in predicting water availability, which is crucial for resource management, agriculture, and flood forecasting.

The TTMS observes and records the ongoing rainfall amounts for surplus or excess rainfall amounts to assess seasonal changes and adjust seasonal and climate forecasts.